Roman Empire

Food and dining

[edit] Main article: Food and dining in the Roman Empire

See also: Grain supply to the city of Rome and Ancient Rome and wine

An Ostian taberna for eating and drinking; the faded painting over the counter pictured eggs, olives, fruit and radishes.[354]

Most apartments in Rome lacked kitchens, though a charcoal brazier could be used for rudimentary cookery.[355][356] Prepared food was sold at pubs and bars, inns, and food stalls (tabernae, cauponae, popinae, thermopolia).[357] Carryout and restaurant dining were for the lower classes; fine dining could be sought only at private dinner parties in well-to-do houses with a chef (archimagirus) and trained kitchen staff,[358] or at banquets hosted by social clubs (collegia).[359]

Most people would have consumed at least 70% of their daily calories in the form of cereals and legumes.[360] Puls (pottage) was considered the aboriginal food of the Romans.[361][362] The basic grain pottage could be elaborated with chopped vegetables, bits of meat, cheese, or herbs to produce dishes similar to polenta or risotto.[363]

Urban populations and the military preferred to consume their grain in the form of bread.[360] Mills and commercial ovens were usually combined in a bakery complex.[364] By the reign of Aurelian, the state had begun to distribute the annona as a daily ration of bread baked in state factories, and added olive oil, wine, and pork to the dole.[346][365][366]

The importance of a good diet to health was recognized by medical writers such as Galen (2nd century AD), whose treatises included one On Barley Soup. Views on nutrition were influenced by schools of thought such as humoral theory.[367]

Roman literature focuses on the dining habits of the upper classes,[368] for whom the evening meal (cena) had important social functions.[369] Guests were entertained in a finely decorated dining room (triclinium), often with a view of the peristyle garden. Diners lounged on couches, leaning on the left elbow. By the late Republic, if not earlier, women dined, reclined, and drank wine along with men.[370]

Still life on a 2nd-century Roman mosaic

The most famous description of a Roman meal is probably Trimalchio's dinner party in the Satyricon, a fictional extravaganza that bears little resemblance to reality even among the most wealthy.[371] The poet Martial describes serving a more plausible dinner, beginning with the gustatio ("tasting" or "appetizer"), which was a salad composed of mallow leaves, lettuce, chopped leeks, mint, arugula, mackerel garnished with rue, sliced eggs, and marinated sow udder. The main course was succulent cuts of kid, beans, greens, a chicken, and leftover ham, followed by a dessert of fresh fruit and vintage wine.[372] The Latin expression for a full-course dinner was ab ovo usque mala, "from the egg to the apples," equivalent to the English "from soup to nuts."[373]

A book-length collection of Roman recipes is attributed to Apicius, a name for several figures in antiquity that became synonymous with "gourmet."[374] Roman "foodies" indulged in wild game, fowl such as peacock and flamingo, large fish (mullet was especially prized), and shellfish. Luxury ingredients were brought by the fleet from the far reaches of empire, from the Parthian frontier to the Straits of Gibraltar.[375]

Refined cuisine could be moralized as a sign of either civilized progress or decadent decline.[376] The early Imperial historian Tacitus contrasted the indulgent luxuries of the Roman table in his day with the simplicity of the Germanic diet of fresh wild meat, foraged fruit, and cheese, unadulterated by imported seasonings and elaborate sauces.[377] Most often, because of the importance of landowning in Roman culture, produce—cereals, legumes, vegetables, and fruit—was considered a more civilized form of food than meat. The Mediterranean staples of bread, wine, and oil were sacralized by Roman Christianity, while Germanic meat consumption became a mark of paganism,[378] as it might be the product of animal sacrifice.

Some philosophers and Christians resisted the demands of the body and the pleasures of food, and adopted fasting as an ideal.[379] Food became simpler in general as urban life in the West diminished, trade routes were disrupted,[378] and the rich retreated to the more limited self-sufficiency of their country estates. As an urban lifestyle came to be associated with decadence, the Church formally discouraged gluttony,[380] and hunting and pastoralism were seen as simple, virtuous ways of life.[378]

Recreation and spectacles

[edit] See also: Ludi, Chariot racing, and Gladiator

Wall painting depicting a sports riot at the amphitheatre of Pompeii, which led to the banning of gladiator combat in the town[381][382]

When Juvenal complained that the Roman people had exchanged their political liberty for "bread and circuses", he was referring to the state-provided grain dole and the circenses, events held in the entertainment venue called a circus in Latin. The largest such venue in Rome was the Circus Maximus, the setting of horse races, chariot races, the equestrian Troy Game, staged beast hunts (venationes), athletic contests, gladiator combat, and historical re-enactments. From earliest times, several religious festivals had featured games (ludi), primarily horse and chariot races (ludi circenses).[383] Although their entertainment value tended to overshadow ritual significance, the races remained part of archaic religious observances that pertained to agriculture, initiation, and the cycle of birth and death.[n 16]

Under Augustus, public entertainments were presented on 77 days of the year; by the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the number of days had expanded to 135.[384] Circus games were preceded by an elaborate parade (pompa circensis) that ended at the venue.[385] Competitive events were held also in smaller venues such as the amphitheatre, which became the characteristic Roman spectacle venue, and stadium. Greek-style athletics included footraces, boxing, wrestling, and the pancratium.[386] Aquatic displays, such as the mock sea battle (naumachia) and a form of "water ballet", were presented in engineered pools.[387] State-supported theatrical events (ludi scaenici) took place on temple steps or in grand stone theatres, or in the smaller enclosed theatre called an odeum.[388]

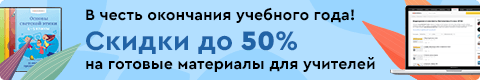

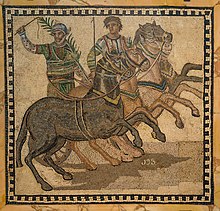

A victor in his four-horse chariot

Circuses were the largest structure regularly built in the Roman world,[389] though the Greeks had their own architectural traditions for the similarly purposed hippodrome. The Flavian Amphitheatre, better known as the Colosseum, became the regular arena for blood sports in Rome after it opened in 80 AD.[390] The circus races continued to be held more frequently.[391] The Circus Maximus could seat around 150,000 spectators, and the Colosseum about 50,000 with standing room for about 10,000 more.[392] Many Roman amphitheatres, circuses and theatres built in cities outside Italy are visible as ruins today.[390] The local ruling elite were responsible for sponsoring spectacles and arena events, which both enhanced their status and drained their resources.[188]

The physical arrangement of the amphitheatre represented the order of Roman society: the emperor presiding in his opulent box; senators and equestrians watching from the advantageous seats reserved for them; women seated at a remove from the action; slaves given the worst places, and everybody else packed in-between.[393][394][395] The crowd could call for an outcome by booing or cheering, but the emperor had the final say. Spectacles could quickly become sites of social and political protest, and emperors sometimes had to deploy force to put down crowd unrest, most notoriously at the Nika riots in the year 532, when troops under Justinian slaughtered thousands.[396][397][398][399]

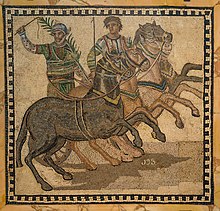

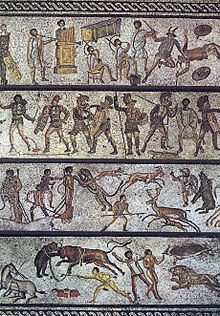

The Zliten mosaic, from a dining room in present-day Libya, depicts a series of arena scenes: from top, musicians playing a Roman tuba, a water pipe organ and two horns; six pairs of gladiators with two referees; four beast fighters; and three convicts condemned to the beasts[400]

The chariot teams were known by the colours they wore, with the Blues and Greens the most popular. Fan loyalty was fierce and at times erupted into sports riots.[397][401][402] Racing was perilous, but charioteers were among the most celebrated and well-compensated athletes.[403] One star of the sport was Diocles, from Lusitania (present-day Portugal), who raced chariots for 24 years and had career earnings of 35 million sesterces.[404][396] Horses had their fans too, and were commemorated in art and inscriptions, sometimes by name.[405][406] The design of Roman circuses was developed to assure that no team had an unfair advantage and to minimize collisions (naufragia, "shipwrecks"),[407][408] which were nonetheless frequent and spectacularly satisfying to the crowd.[409][410] The races retained a magical aura through their early association with chthonic rituals: circus images were considered protective or lucky, curse tablets have been found buried at the site of racetracks, and charioteers were often suspected of sorcery.[396][411][412][413][414] Chariot racing continued into the Byzantine period under imperial sponsorship, but the decline of cities in the 6th and 7th centuries led to its eventual demise.[389]

The Romans thought gladiator contests had originated with funeral games and sacrifices in which select captive warriors were forced to fight to expiate the deaths of noble Romans. Some of the earliest styles of gladiator fighting had ethnic designations such as "Thracian" or "Gallic".[368][415][416] The staged combats were considered munera, "services, offerings, benefactions", initially distinct from the festival games (ludi).[415][416]

Throughout his 40-year reign, Augustus presented eight gladiator shows in which a total of 10,000 men fought, as well as 26 staged beast hunts that resulted in the deaths of 3,500 animals.[417][418][419] To mark the opening of the Colosseum, the emperor Titus presented 100 days of arena events, with 3,000 gladiators competing on a single day.[390][420][421] Roman fascination with gladiators is indicated by how widely they are depicted on mosaics, wall paintings, lamps, and in graffiti.[418]

Gladiators were trained combatants who might be slaves, convicts, or free volunteers.[422] Death was not a necessary or even desirable outcome in matches between these highly skilled fighters, whose training represented a costly and time-consuming investment.[421][423][424] By contrast, noxii were convicts sentenced to the arena with little or no training, often unarmed, and with no expectation of survival. Physical suffering and humiliation were considered appropriate retributive justice for the crimes they had committed.[188] These executions were sometimes staged or ritualized as re-enactments of myths, and amphitheatres were equipped with elaborate stage machinery to create special effects.[188][425][426] Tertullian considered deaths in the arena to be nothing more than a dressed-up form of human sacrifice.[427][428][429]

Modern scholars have found the pleasure Romans took in the "theatre of life and death"[430] to be one of the more difficult aspects of their civilization to understand and explain.[431][432] The younger Pliny rationalized gladiator spectacles as good for the people, a way "to inspire them to face honourable wounds and despise death, by exhibiting love of glory and desire for victory even in the bodies of slaves and criminals".[433][434] Some Romans such as Seneca were critical of the brutal spectacles, but found virtue in the courage and dignity of the defeated fighter rather than in victory[435]—an attitude that finds its fullest expression with the Christians martyred in the arena. Even martyr literature, however, offers "detailed, indeed luxuriant, descriptions of bodily suffering",[436] and became a popular genre at times indistinguishable from fiction.[437][438][439][440][441][442]

Personal training and play

[edit]

Boys and girls playing ball games (2nd-century relief from the Louvre)

In the plural, ludi almost always refers to the large-scale spectator games. The singular ludus, "play, game, sport, training," had a wide range of meanings such as "word play," "theatrical performance," "board game," "primary school," and even "gladiator training school" (as in Ludus Magnus, the largest such training camp at Rome).[443][444]

Activities for children and young people included hoop rolling and knucklebones (astragali or "jacks"). The sarcophagi of children often show them playing games. Girls had dolls, typically 15–16 cm tall with jointed limbs, made of materials such as wood, terracotta, and especially bone and ivory.[445] Ball games include trigon, which required dexterity, and harpastum, a rougher sport.[446] Pets appear often on children's memorials and in literature, including birds, dogs, cats, goats, sheep, rabbits and geese.[447]

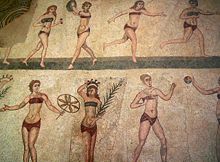

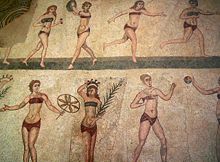

So-called "bikini girls" mosaic from the Villa del Casale, Roman Sicily, 4th century

Stone game board from Aphrodisias: boards could also be made of wood, with deluxe versions in costly materials such as ivory; game pieces or counters were bone, glass, or polished stone, and might be coloured or have markings or images[448]

After adolescence, most physical training for males was of a military nature. The Campus Martius originally was an exercise field where young men developed the skills of horsemanship and warfare. Hunting was also considered an appropriate pastime. According to Plutarch, conservative Romans disapproved of Greek-style athletics that promoted a fine body for its own sake, and condemned Nero's efforts to encourage gymnastic games in the Greek manner.[449]

Some women trained as gymnasts and dancers, and a rare few as female gladiators. The famous "bikini girls" mosaic shows young women engaging in apparatus routines that might be compared to rhythmic gymnastics.[n 17][450] Women, in general, were encouraged to maintain their health through activities such as playing ball, swimming, walking, reading aloud (as a breathing exercise), riding in vehicles, and travel.[451]

People of all ages played board games pitting two players against each other, including latrunculi ("Raiders"), a game of strategy in which opponents coordinated the movements and capture of multiple game pieces, and XII scripta ("Twelve Marks"), involving dice and arranging pieces on a grid of letters or words.[452] A game referred to as alea (dice) or tabula (the board), to which the emperor Claudius was notoriously addicted, may have been similar to backgammon, using a dice-cup (pyrgus).[448] Playing with dice as a form of gambling was disapproved of, but was a popular pastime during the December festival of the Saturnalia with its carnival, norms-overturned atmosphere.

Clothing

[edit] Main article: Clothing in ancient Rome

In a status-conscious society like that of the Romans, clothing and personal adornment gave immediate visual clues about the etiquette of interacting with the wearer.[453] Wearing the correct clothing was supposed to reflect a society in good order.[454] The toga was the distinctive national garment of the Roman male citizen, but it was heavy and impractical, worn mainly for conducting political business and religious rites, and for going to court.[455][456] The clothing Romans wore ordinarily was dark or colourful, and the most common male attire seen daily throughout the provinces would have been tunics, cloaks, and in some regions trousers.[457] The study of how Romans dressed in daily life is complicated by a lack of direct evidence, since portraiture may show the subject in clothing with symbolic value, and surviving textiles from the period are rare.[456][458][459]

Women from the wall painting at the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii

Claudius wearing an early Imperial toga (see a later, more structured toga above), and the pallium as worn by a priest of Serapis,[460] sometimes identified as the emperor Julian

The basic garment for all Romans, regardless of gender or wealth, was the simple sleeved tunic. The length differed by wearer: a man's reached mid-calf, but a soldier's was somewhat shorter; a woman's fell to her feet, and a child's to its knees.[461] The tunics of poor people and labouring slaves were made from coarse wool in natural, dull shades, with the length determined by the type of work they did. Finer tunics were made of lightweight wool or linen. A man who belonged to the senatorial or equestrian order wore a tunic with two purple stripes (clavi) woven vertically into the fabric: the wider the stripe, the higher the wearer's status.[461] Other garments could be layered over the tunic.

The Imperial toga was a "vast expanse" of semi-circular white wool that could not be put on and draped correctly without assistance.[455] In his work on oratory, Quintilian describes in detail how the public speaker ought to orchestrate his gestures in relation to his toga.[454][456][462] In art, the toga is shown with the long end dipping between the feet, a deep curved fold in front, and a bulbous flap at the midsection.[456] The drapery became more intricate and structured over time, with the cloth forming a tight roll across the chest in later periods.[463] The toga praetexta, with a purple or purplish-red stripe representing inviolability, was worn by children who had not come of age, curule magistrates, and state priests. Only the emperor could wear an all-purple toga (toga picta).[464]

In the 2nd century, emperors and men of status are often portrayed wearing the pallium, an originally Greek mantle (himation) folded tightly around the body. Women are also portrayed in the pallium. Tertullian considered the pallium an appropriate garment both for Christians, in contrast to the toga, and for educated people, since it was associated with philosophers.[454][456][465] By the 4th century, the toga had been more or less replaced by the pallium as a garment that embodied social unity.[466]

Roman clothing styles changed over time, though not as rapidly as fashions today.[467] In the Dominate, clothing worn by both soldiers and government bureaucrats became highly decorated, with woven or embroidered stripes (clavi) and circular roundels (orbiculi) applied to tunics and cloaks. These decorative elements consisted of geometrical patterns, stylized plant motifs, and in more elaborate examples, human or animal figures.[468] The use of silk increased, and courtiers of the later Empire wore elaborate silk robes. The militarization of Roman society, and the waning of cultural life based on urban ideals, affected habits of dress: heavy military-style belts were worn by bureaucrats as well as soldiers, and the toga was abandoned.[469]