Roman Empire

Government and military[edit] Main article: Constitution of the Roman Empire

Forum of Gerasa (Jerash in present-day Jordan), with columns marking a covered walkway (stoa) for vendor stalls, and a semicircular space for public speaking

The three major elements of the Imperial Roman state were the central government, the military, and the provincial government.[190] The military established control of a territory through war, but after a city or people was brought under treaty, the military mission turned to policing: protecting Roman citizens (after 212 AD, all freeborn inhabitants of the Empire), the agricultural fields that fed them, and religious sites.[191] Without modern instruments of either mass communication or mass destruction, the Romans lacked sufficient manpower or resources to impose their rule through force alone. Cooperation with local power elites was necessary to maintain order, collect information, and extract revenue. The Romans often exploited internal political divisions by supporting one faction over another: in the view of Plutarch, "it was discord between factions within cities that led to the loss of self-governance".[192][193][194]

Communities with demonstrated loyalty to Rome retained their own laws, could collect their own taxes locally, and in exceptional cases were exempt from Roman taxation. Legal privileges and relative independence were an incentive to remain in good standing with Rome.[195] Roman government was thus limited, but efficient in its use of the resources available to it.[196]

Central government

[edit] See also: Roman emperor and Senate of the Roman Empire

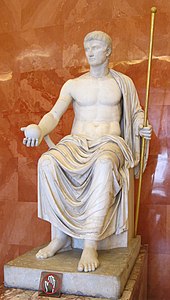

Reconstructed statue of Augustus as Jove, holding scepter and orb (first half of 1st century AD).[197]

The Imperial cult of ancient Rome identified emperors and some members of their families with the divinely sanctioned authority (auctoritas) of the Roman State. The rite of apotheosis (also called consecratio) signified the deceased emperor's deification and acknowledged his role as father of the people similar to the concept of a pater familias' soul or manes being honoured by his sons.[198]

The dominance of the emperor was based on the consolidation of certain powers from several republican offices, including the inviolability of the tribunes of the people and the authority of the censors to manipulate the hierarchy of Roman society.[199] The emperor also made himself the central religious authority as Pontifex Maximus, and centralized the right to declare war, ratify treaties, and negotiate with foreign leaders.[200] While these functions were clearly defined during the Principate, the emperor's powers over time became less constitutional and more monarchical, culminating in the Dominate.[201]

Antoninus Pius (reigned 138–161), wearing a toga (Hermitage Museum)

The emperor was the ultimate authority in policy- and decision-making, but in the early Principate, he was expected to be accessible to individuals from all walks of life and to deal personally with official business and petitions. A bureaucracy formed around him only gradually.[202] The Julio-Claudian emperors relied on an informal body of advisors that included not only senators and equestrians, but trusted slaves and freedmen.[203] After Nero, the unofficial influence of the latter was regarded with suspicion, and the emperor's council (consilium) became subject to official appointment for the sake of greater transparency.[204] Though the Senate took a lead in policy discussions until the end of the Antonine dynasty, equestrians played an increasingly important role in the consilium.[205] The women of the emperor's family often intervened directly in his decisions. Plotina exercised influence on both her husband Trajan and his successor Hadrian. Her influence was advertised by having her letters on official matters published, as a sign that the emperor was reasonable in his exercise of authority and listened to his people.[206]

Access to the emperor by others might be gained at the daily reception (salutatio), a development of the traditional homage a client paid to his patron; public banquets hosted at the palace; and religious ceremonies. The common people who lacked this access could manifest their general approval or displeasure as a group at the games held in large venues.[207] By the 4th century, as urban centres decayed, the Christian emperors became remote figureheads who issued general rulings, no longer responding to individual petitions.[208]

Although the Senate could do little short of assassination and open rebellion to contravene the will of the emperor, it survived the Augustan restoration and the turbulent Year of Four Emperors to retain its symbolic political centrality during the Principate.[209] The Senate legitimated the emperor's rule, and the emperor needed the experience of senators as legates (legati) to serve as generals, diplomats, and administrators.[209][210] A successful career required competence as an administrator and remaining in favour with the emperor, or over time perhaps multiple emperors.[175]

The practical source of an emperor's power and authority was the military. The legionaries were paid by the Imperial treasury, and swore an annual military oath of loyalty to the emperor (sacramentum).[211] The death of an emperor led to a crucial period of uncertainty and crisis. Most emperors indicated their choice of successor, usually a close family member or adopted heir. The new emperor had to seek a swift acknowledgement of his status and authority to stabilize the political landscape. No emperor could hope to survive, much less to reign, without the allegiance and loyalty of the Praetorian Guard and of the legions. To secure their loyalty, several emperors paid the donativum, a monetary reward. In theory, the Senate was entitled to choose the new emperor, but did so mindful of acclamation by the army or Praetorians.[210]

Military

[edit]

The Roman empire under Hadrian (ruled 117–138) showing the location of the Roman legions deployed in 125 AD

Main articles: Imperial Roman army and Structural history of the Roman military

After the Punic Wars, the Imperial Roman army was composed of professional soldiers who volunteered for 20 years of active duty and five as reserves. The transition to a professional military had begun during the late Republic and was one of the many profound shifts away from republicanism, under which an army of conscripts had exercised their responsibilities as citizens in defending the homeland in a campaign against a specific threat. For Imperial Rome, the military was a full-time career in itself.[212] The Romans expanded their war machine by "organizing the communities that they conquered in Italy into a system that generated huge reservoirs of manpower for their army... Their main demand of all defeated enemies was they provide men for the Roman army every year."[213]

The primary mission of the Roman military of the early empire was to preserve the Pax Romana.[214] The three major divisions of the military were:

the garrison at Rome, which includes both the Praetorians and the vigiles who functioned as police and firefighters;

the provincial army, comprising the Roman legions and the auxiliaries provided by the provinces (auxilia);

the navy.

The pervasiveness of military garrisons throughout the Empire was a major influence in the process of cultural exchange and assimilation known as "Romanization," particularly in regard to politics, the economy, and religion.[215] Knowledge of the Roman military comes from a wide range of sources: Greek and Roman literary texts; coins with military themes; papyri preserving military documents; monuments such as Trajan's Column and triumphal arches, which feature artistic depictions of both fighting men and military machines; the archeology of military burials, battle sites, and camps; and inscriptions, including military diplomas, epitaphs, and dedications.[216]

Through his military reforms, which included consolidating or disbanding units of questionable loyalty, Augustus changed and regularized the legion, down to the hobnail pattern on the soles of army boots. A legion was organized into ten cohorts, each of which comprised six centuries, with a century further made up of ten squads (contubernia); the exact size of the Imperial legion, which is most likely to have been determined by logistics, has been estimated to range from 4,800 to 5,280.[217]

Relief panel from Trajan's Column in Rome, showing the building of a fort and the reception of a Dacian embassy

In 9 AD, Germanic tribes wiped out three full legions in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. This disastrous event reduced the number of legions to 25. The total of the legions would later be increased again and for the next 300 years always be a little above or below 30.[218] The army had about 300,000 soldiers in the 1st century, and under 400,000 in the 2nd, "significantly smaller" than the collective armed forces of the territories it conquered. No more than 2% of adult males living in the Empire served in the Imperial army.[219]

Augustus also created the Praetorian Guard: nine cohorts, ostensibly to maintain the public peace, which were garrisoned in Italy. Better paid than the legionaries, the Praetorians served only sixteen years.[220]

The auxilia were recruited from among the non-citizens. Organized in smaller units of roughly cohort strength, they were paid less than the legionaries, and after 25 years of service were rewarded with Roman citizenship, also extended to their sons. According to Tacitus[221] there were roughly as many auxiliaries as there were legionaries. The auxilia thus amounted to around 125,000 men, implying approximately 250 auxiliary regiments.[222] The Roman cavalry of the earliest Empire were primarily from Celtic, Hispanic or Germanic areas. Several aspects of training and equipment, such as the four-horned saddle, derived from the Celts, as noted by Arrian and indicated by archeology.[223][224]

The Roman navy (Latin: classis, "fleet") not only aided in the supply and transport of the legions but also helped in the protection of the frontiers along the rivers Rhine and Danube. Another of its duties was the protection of the crucial maritime trade routes against the threat of pirates. It patrolled the whole of the Mediterranean, parts of the North Atlantic coasts, and the Black Sea. Nevertheless, the army was considered the senior and more prestigious branch.[225]

Provincial government

[edit]

The Pula Arena in Croatia is one of the largest and most intact of the remaining Roman amphitheatres.

An annexed territory became a province in a three-step process: making a register of cities, taking a census of the population, and surveying the land.[226] Further government recordkeeping included births and deaths, real estate transactions, taxes, and juridical proceedings.[227] In the 1st and 2nd centuries, the central government sent out around 160 officials each year to govern outside Italy.[11] Among these officials were the "Roman governors", as they are called in English: either magistrates elected at Rome who in the name of the Roman people governed senatorial provinces; or governors, usually of equestrian rank, who held their imperium on behalf of the emperor in provinces excluded from senatorial control, most notably Roman Egypt.[228] A governor had to make himself accessible to the people he governed, but he could delegate various duties.[229] His staff, however, was minimal: his official attendants (apparitores), including lictors, heralds, messengers, scribes, and bodyguards; legates, both civil and military, usually of equestrian rank; and friends, ranging in age and experience, who accompanied him unofficially.[229]

Other officials were appointed as supervisors of government finances.[11] Separating fiscal responsibility from justice and administration was a reform of the Imperial era. Under the Republic, provincial governors and tax farmers could exploit local populations for personal gain more freely.[230] Equestrian procurators, whose authority was originally "extra-judicial and extra-constitutional," managed both state-owned property and the vast personal property of the emperor (res privata).[229] Because Roman government officials were few in number, a provincial who needed help with a legal dispute or criminal case might seek out any Roman perceived to have some official capacity, such as a procurator or a military officer, including centurions down to the lowly stationarii or military police.[229][231]

Roman law

[edit] Main article: Roman law

Roman portraiture frescos from Pompeii, 1st century AD, depicting two different men wearing laurel wreaths, one holding the rotulus (blondish figure, left), the other a volumen (brunet figure, right), both made of papyrus

Roman courts held original jurisdiction over cases involving Roman citizens throughout the empire, but there were too few judicial functionaries to impose Roman law uniformly in the provinces. Most parts of the Eastern empire already had well-established law codes and juridical procedures.[105] In general, it was Roman policy to respect the mos regionis ("regional tradition" or "law of the land") and to regard local laws as a source of legal precedent and social stability.[105][232] The compatibility of Roman and local law was thought to reflect an underlying ius gentium, the "law of nations" or international law regarded as common and customary among all human communities.[233] If the particulars of provincial law conflicted with Roman law or custom, Roman courts heard appeals, and the emperor held final authority to render a decision.[105][232][234]

In the West, law had been administered on a highly localized or tribal basis, and private property rights may have been a novelty of the Roman era, particularly among Celtic peoples. Roman law facilitated the acquisition of wealth by a pro-Roman elite who found their new privileges as citizens to be advantageous.[105] The extension of universal citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Empire in 212 required the uniform application of Roman law, replacing the local law codes that had applied to non-citizens. Diocletian's efforts to stabilize the Empire after the Crisis of the Third Century included two major compilations of law in four years, the Codex Gregorianus and the Codex Hermogenianus, to guide provincial administrators in setting consistent legal standards.[235]

The pervasive exercise of Roman law throughout Western Europe led to its enormous influence on the Western legal tradition, reflected by the continued use of Latin legal terminology in modern law.

Taxation

[edit] Taxation under the Empire amounted to about 5% of the Empire's gross product.[236] The typical tax rate paid by individuals ranged from 2 to 5%.[237] The tax code was "bewildering" in its complicated system of direct and indirect taxes, some paid in cash and some in kind. Taxes might be specific to a province, or kinds of properties such as fisheries or salt evaporation ponds; they might be in effect for a limited time.[238] Tax collection was justified by the need to maintain the military,[45][239] and taxpayers sometimes got a refund if the army captured a surplus of booty.[239] In-kind taxes were accepted from less-monetized areas, particularly those who could supply grain or goods to army camps.[240]

Personification of the River Nile and his children, from the Temple of Serapis and Isis in Rome (1st century AD)

The primary source of direct tax revenue was individuals, who paid a poll tax and a tax on their land, construed as a tax on its produce or productive capacity.[237] Supplemental forms could be filed by those eligible for certain exemptions; for example, Egyptian farmers could register fields as fallow and tax-exempt depending on flood patterns of the Nile.[241] Tax obligations were determined by the census, which required each head of household to appear before the presiding official and provide a headcount of his household, as well as an accounting of property he owned that was suitable for agriculture or habitation.[241]

A major source of indirect-tax revenue was the portoria, customs and tolls on imports and exports, including among provinces.[237] Special taxes were levied on the slave trade. Towards the end of his reign, Augustus instituted a 4% tax on the sale of slaves,[242] which Nero shifted from the purchaser to the dealers, who responded by raising their prices.[243] An owner who manumitted a slave paid a "freedom tax", calculated at 5% of value.[244]

An inheritance tax of 5% was assessed when Roman citizens above a certain net worth left property to anyone but members of their immediate family. Revenues from the estate tax and from a 1% sales tax on auctions went towards the veterans' pension fund (aerarium militare).[237]

Low taxes helped the Roman aristocracy increase their wealth, which equalled or exceeded the revenues of the central government. An emperor sometimes replenished his treasury by confiscating the estates of the "super-rich", but in the later period, the resistance of the wealthy to paying taxes was one of the factors contributing to the collapse of the Empire.[45]

Economy[edit] Main article: Roman economy

A green Roman glass cup unearthed from an Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD) tomb in Guangxi, southern China; the earliest Roman glassware found in China was discovered in a Western Han tomb in Guangzhou, dated to the early 1st century BC, and ostensibly came via the maritime route through the South China Sea[245]

Moses Finley was the chief proponent of the primitivist view that the Roman economy was "underdeveloped and underachieving," characterized by subsistence agriculture; urban centres that consumed more than they produced in terms of trade and industry; low-status artisans; slowly developing technology; and a "lack of economic rationality."[246] Current views are more complex. Territorial conquests permitted a large-scale reorganization of land use that resulted in agricultural surplus and specialization, particularly in north Africa.[247] Some cities were known for particular industries or commercial activities, and the scale of building in urban areas indicates a significant construction industry.[247] Papyri preserve complex accounting methods that suggest elements of economic rationalism,[248] and the Empire was highly monetized.[249] Although the means of communication and transport were limited in antiquity, transportation in the 1st and 2nd centuries expanded greatly, and trade routes connected regional economies.[250] The supply contracts for the army, which pervaded every part of the Empire, drew on local suppliers near the base (castrum), throughout the province, and across provincial borders.[251] The Empire is perhaps best thought of as a network of regional economies, based on a form of "political capitalism" in which the state monitored and regulated commerce to assure its own revenues.[252] Economic growth, though not comparable to modern economies, was greater than that of most other societies prior to industrialization.[248]

Socially, economic dynamism opened up one of the avenues of social mobility in the Roman Empire. Social advancement was thus not dependent solely on birth, patronage, good luck, or even extraordinary ability. Although aristocratic values permeated traditional elite society, a strong tendency towards plutocracy is indicated by the wealth requirements for census rank. Prestige could be obtained through investing one's wealth in ways that advertised it appropriately: grand country estates or townhouses, durable luxury items such as jewels and silverware, public entertainments, funerary monuments for family members or coworkers, and religious dedications such as altars. Guilds (collegia) and corporations (corpora) provided support for individuals to succeed through networking, sharing sound business practices, and a willingness to work.[182]

Currency and banking

[edit] See also: Roman currency and Roman finance

The early Empire was monetized to a near-universal extent, in the sense of using money as a way to express prices and debts.[253] The sestertius (plural sestertii, English "sesterces", symbolized as HS) was the basic unit of reckoning value into the 4th century,[254] though the silver denarius, worth four sesterces, was used also for accounting beginning in the Severan dynasty.[255] The smallest coin commonly circulated was the bronze as (plural asses), one-fourth sestertius.[256] Bullion and ingots seem not to have counted as pecunia, "money," and were used only on the frontiers for transacting business or buying property. Romans in the 1st and 2nd centuries counted coins, rather than weighing them—an indication that the coin was valued on its face, not for its metal content. This tendency towards fiat money led eventually to the debasement of Roman coinage, with consequences in the later Empire.[257] The standardization of money throughout the Empire promoted trade and market integration.[253] The high amount of metal coinage in circulation increased the money supply for trading or saving.[258]

| Currency denominations[259] |

| 211 BC | 14 AD | 286–296 AD |

| Denarius = 10 asses | Aureus = 25 denarii | Aurei = 60 per pound of gold |

| Sesterce = 5 asses | Denarii = 16 asses | Silver coins (contemporary name unknown) = 96 to a pound of silver |

| Sestertius = 2.5 asses | Sesterces = 4 asses | Bronze coins (contemporary name unknown) = value unknown |

| Asses = 1 | Asses = 1 |

|

Rome had no central bank, and regulation of the banking system was minimal. Banks of classical antiquity typically kept less in reserves than the full total of customers' deposits. A typical bank had fairly limited capital, and often only one principal, though a bank might have as many as six to fifteen principals. Seneca assumes that anyone involved in commerce needs access to credit.[257]

Solidus issued under Constantine II, and on the reverse Victoria, one of the last deities to appear on Roman coins, gradually transforming into an angel under Christian rule[260]

A professional deposit banker (argentarius, coactor argentarius, or later nummularius) received and held deposits for a fixed or indefinite term, and lent money to third parties. The senatorial elite were involved heavily in private lending, both as creditors and borrowers, making loans from their personal fortunes on the basis of social connections.[257][261] The holder of a debt could use it as a means of payment by transferring it to another party, without cash changing hands. Although it has sometimes been thought that ancient Rome lacked "paper" or documentary transactions, the system of banks throughout the Empire also permitted the exchange of very large sums without the physical transfer of coins, in part because of the risks of moving large amounts of cash, particularly by sea. Only one serious credit shortage is known to have occurred in the early Empire, a credit crisis in 33 AD that put a number of senators at risk; the central government rescued the market through a loan of 100 million HS made by the emperor Tiberius to the banks (mensae).[262] Generally, available capital exceeded the amount needed by borrowers.[257] The central government itself did not borrow money, and without public debt had to fund deficits from cash reserves.[263]

Emperors of the Antonine and Severan dynasties overall debased the currency, particularly the denarius, under the pressures of meeting military payrolls.[254] Sudden inflation during the reign of Commodus damaged the credit market.[257] In the mid-200s, the supply of specie contracted sharply.[254] Conditions during the Crisis of the Third Century—such as reductions in long-distance trade, disruption of mining operations, and the physical transfer of gold coinage outside the empire by invading enemies—greatly diminished the money supply and the banking sector by the year 300.[254][257] Although Roman coinage had long been fiat money or fiduciary currency, general economic anxieties came to a head under Aurelian, and bankers lost confidence in coins legitimately issued by the central government. Despite Diocletian's introduction of the gold solidus and monetary reforms, the credit market of the Empire never recovered its former robustness.[257]

Mining and metallurgy

[edit] Main article: Roman metallurgy

See also: Mining in Roman Britain

Landscape resulting from the ruina montium mining technique at Las Médulas, Spain, one of the most important gold mines in the Roman Empire

The main mining regions of the Empire were the Iberian Peninsula (gold, silver, copper, tin, lead); Gaul (gold, silver, iron); Britain (mainly iron, lead, tin), the Danubian provinces (gold, iron); Macedonia and Thrace (gold, silver); and Asia Minor (gold, silver, iron, tin). Intensive large-scale mining—of alluvial deposits, and by means of open-cast mining and underground mining—took place from the reign of Augustus up to the early 3rd century AD, when the instability of the Empire disrupted production. The gold mines of Dacia, for instance, were no longer available for Roman exploitation after the province was surrendered in 271. Mining seems to have resumed to some extent during the 4th century.[264]

Hydraulic mining, which Pliny referred to as ruina montium ("ruin of the mountains"), allowed base and precious metals to be extracted on a proto-industrial scale.[265] The total annual iron output is estimated at 82,500 tonnes.[266][267][268] Copper was produced at an annual rate of 15,000 t,[265][269] and lead at 80,000 t,[265][270][271] both production levels unmatched until the Industrial Revolution;[269][270][271][272] Hispania alone had a 40% share in world lead production.[270] The high lead output was a by-product of extensive silver mining which reached 200 t per annum. At its peak around the mid-2nd century AD, the Roman silver stock is estimated at 10,000 t, five to ten times larger than the combined silver mass of medieval Europe and the Caliphate around 800 AD.[271][273] As an indication of the scale of Roman metal production, lead pollution in the Greenland ice sheet quadrupled over its prehistoric levels during the Imperial era and dropped again thereafter.[274]

Transportation and communication

[edit] See also: Cursus publicus

The Tabula Peutingeriana (Latin for "The Peutinger Map") an Itinerarium, often assumed to be based on the Roman cursus publicus, the network of state-maintained roads.

The Roman Empire completely encircled the Mediterranean, which they called "our sea" (mare nostrum).[275] Roman sailing vessels navigated the Mediterranean as well as the major rivers of the Empire, including the Guadalquivir, Ebro, Rhône, Rhine, Tiber and Nile.[276] Transport by water was preferred where possible, and moving commodities by land was more difficult.[277] Vehicles, wheels, and ships indicate the existence of a great number of skilled woodworkers.[278]

Land transport utilized the advanced system of Roman roads, which were called "viae". These roads were primarily built for military purposes,[279] but also served commercial ends. The in-kind taxes paid by communities included the provision of personnel, animals, or vehicles for the cursus publicus, the state mail and transport service established by Augustus.[240] Relay stations were located along the roads every seven to twelve Roman miles, and tended to grow into villages or trading posts.[280] A mansio (plural mansiones) was a privately run service station franchised by the imperial bureaucracy for the cursus publicus. The support staff at such a facility included muleteers, secretaries, blacksmiths, cartwrights, a veterinarian, and a few military police and couriers. The distance between mansiones was determined by how far a wagon could travel in a day.[280] Mules were the animal most often used for pulling carts, travelling about 4 mph.[281] As an example of the pace of communication, it took a messenger a minimum of nine days to travel to Rome from Mainz in the province of Germania Superior, even on a matter of urgency.[282] In addition to the mansiones, some taverns offered accommodation as well as food and drink; one recorded tab for a stay showed charges for wine, bread, mule feed, and the services of a prostitute.[283]

Trade and commodities

[edit] See also: Roman commerce, Indo-Roman trade and relations, and Sino-Roman relations

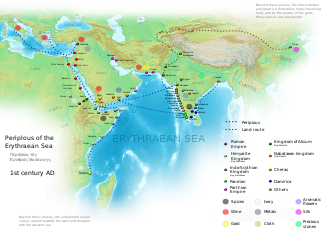

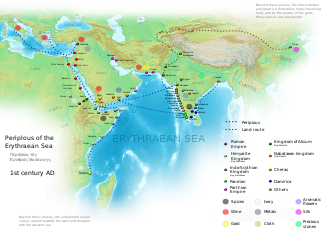

A map of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a Greco-Roman Periplus

Roman provinces traded among themselves, but trade extended outside the frontiers to regions as far away as China and India.[276] The main commodity was grain.[284] Chinese trade was mostly conducted overland through middle men along the Silk Road; Indian trade, however, also occurred by sea from Egyptian ports on the Red Sea. Along these trade paths, the horse, upon which Roman expansion and commerce depended, was one of the main channels through which disease spread.[285] Also in transit for trade were olive oil, various foodstuffs, garum (fish sauce), slaves, ore and manufactured metal objects, fibres and textiles, timber, pottery, glassware, marble, papyrus, spices and materia medica, ivory, pearls, and gemstones.[286]

Though most provinces were capable of producing wine, regional varietals were desirable and wine was a central item of trade. Shortages of vin ordinaire were rare.[287][288] The major suppliers for the city of Rome were the west coast of Italy, southern Gaul, the Tarraconensis region of Hispania, and Crete. Alexandria, the second-largest city, imported wine from Laodicea in Syria and the Aegean.[289] At the retail level, taverns or specialty wine shops (vinaria) sold wine by the jug for carryout and by the drink on premises, with price ranges reflecting quality.[290]

Labour and occupations

[edit]

Workers at a cloth-processing shop, in a painting from the fullonica of Veranius Hypsaeus in Pompeii

Inscriptions record 268 different occupations in the city of Rome, and 85 in Pompeii.[219] Professional associations or trade guilds (collegia) are attested for a wide range of occupations, including fishermen (piscatores), salt merchants (salinatores), olive oil dealers (olivarii), entertainers (scaenici), cattle dealers (pecuarii), goldsmiths (aurifices), teamsters (asinarii or muliones), and stonecutters (lapidarii). These are sometimes quite specialized: one collegium at Rome was strictly limited to craftsmen who worked in ivory and citrus wood.[182]

Work performed by slaves falls into five general categories: domestic, with epitaphs recording at least 55 different household jobs; imperial or public service; urban crafts and services; agriculture; and mining. Convicts provided much of the labour in the mines or quarries, where conditions were notoriously brutal.[291] In practice, there was little division of labour between slave and free,[105] and most workers were illiterate and without special skills.[292] The greatest number of common labourers were employed in agriculture: in the Italian system of industrial farming (latifundia), these may have been mostly slaves, but throughout the Empire, slave farm labour was probably less important than other forms of dependent labour by people who were technically not enslaved.[105]

Textile and clothing production was a major source of employment. Both textiles and finished garments were traded among the peoples of the Empire, whose products were often named for them or a particular town, rather like a fashion "label".[293] Better ready-to-wear was exported by businessmen (negotiatores or mercatores) who were often well-to-do residents of the production centres.[294] Finished garments might be retailed by their sales agents, who travelled to potential customers, or by vestiarii, clothing dealers who were mostly freedmen; or they might be peddled by itinerant merchants.[294] In Egypt, textile producers could run prosperous small businesses employing apprentices, free workers earning wages, and slaves.[295] The fullers (fullones) and dye workers (coloratores) had their own guilds.[296] Centonarii were guild workers who specialized in textile production and the recycling of old clothes into pieced goods.[n 14]

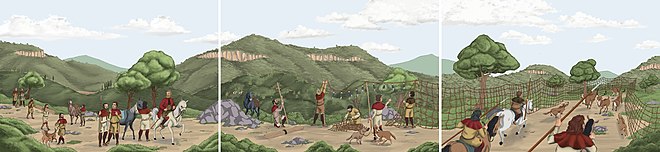

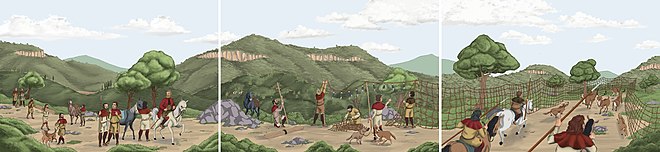

Roman hunters during the preparations, set-up of traps, and in-action hunting near Tarraco

GDP and income distribution

[edit] Further information: Roman economy § Gross domestic product

Economic historians vary in their calculations of the gross domestic product of the Roman economy during the Principate.[297] In the sample years of 14, 100, and 150 AD, estimates of per capita GDP range from 166 to 380 HS. The GDP per capita of Italy is estimated as 40[298] to 66%[299] higher than in the rest of the Empire, due to tax transfers from the provinces and the concentration of elite income in the heartland. In regard to Italy, "there can be little doubt that the lower classes of Pompeii, Herculaneum and other provincial towns of the Roman Empire enjoyed a high standard of living not equaled again in Western Europe until the 19th century AD".[300]

In the Scheidel–Friesen economic model, the total annual income generated by the Empire is placed at nearly 20 billion HS, with about 5% extracted by central and local government. Households in the top 1.5% of income distribution captured about 20% of income. Another 20% went to about 10% of the population who can be characterized as a non-elite middle. The remaining "vast majority" produced more than half of the total income, but lived near subsistence.[301] The elite were 1.2–1.7% and the middling "who enjoyed modest, comfortable levels of existence but not extreme wealth amounted to 6–12% (...) while the vast majority lived around subsistence".[302]