Материал по предмету «Страноведение» 10 класс.

American Revolution. Forming a Republic.

Шалдыбина М.Л., учитель английского языка, лингвистическая гимназия № 36, Луганск.

FIGHTING FOR INDEPENDENCE

Colonies on the Eve of the Revolution

By the middle of the 18th century, English colonies in North America were still closely linked to Great Britain, though the resistance to mother country inside the colonies grew. The period between 1760 and 1775, was a time of growing gap between the mother country and colonies when taxes, trade restrictions, political decisions at a distance, and violations on religious and social rights began to anger colonists.

Before American Revolution actually started, it was, as John Adams said, "in the minds of people", who wanted progress for the colonies rather than independence from Britain. While the tension between Britain and colonies was constantly growing, colonial politicians still tried to preserve peaceful relations with mother country and even when the fighting started, there were many people, who were reluctant to sever political relationship with England.

There were some important events that changed relations between England and colonies and altered the balance of power in North America—a series of wars, which ended with imperial reorganization and new taxes, tariff duties and other restrictions levied by British Parliament on American colonies.

T he French and Indian War

he French and Indian War

During the 18th century, France and Britain were engaged in a series of wars, the most important of which for colonies in North America became the Seven Years War in 1754. In America this war got the other name — the French and Indian War.

The war started at the time, when the French and Spanish had already established strong positions around the boundaries of English colonies. Spain spread its outpost in Florida and along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. while the French possessed very important interior territories along the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River to New Orleans. The French also established strong relationship with local Indian tribes so they protected the fur trade from the English rivals.

The war started as fighting for west frontiers of English colonies and soon developed into a struggle for nominal control of the North American continent. The first armed clash between the French army and Virginia militiamen, which took place in 1754 in Pennsylvania, was lost by the colonists. The conflict had to be resolved — so British officials insisted on the meeting of the delegates from seven northern and middle colonies with the representatives of the Indian tribes on the Albany Congress. Though the relations with the Indians were not improved, the Congress adopted an important resolution — the .Albany Plan of Union, which aimed to establish an elected intercolonial legislature with the power to tax. The plan developed by Benjamin Franklin, called for the Union, but was unanimously rejected by colonial governments as they feared loss of autonomy.

The war, which began in North America, soon involved half of the world. It was fought in North America till 1760, during this time the British won decisive battles in Quebec and took Montreal, the last French stronghold. After 1760, the war continued for three more years in the Caribbean, India, and Europe.

The war ended with the Peace of Paris, signed in 1763. By this treaty France ceded its major North American holdings to Britain. Britain also got Spanish Florida, whereas Spain extended its possessions to French Louisiana.

Now victorious Britain faced another problem — how to govern such vast territories inhabited by not only English-speaking Protestants, but also by French-speaking Catholics from Quebec and large numbers of Indians. In order to maintain control over the territories the British issued a proclamation, which forbade the colonists to move into Indian lands.

The proclamation set up western boundaries of the colonies and aimed to restrict settlements that could provoke new wars with Indian tribes. Colonists had already established farms west from the proclamation line, they viewed the Proclamation Line as a disregard of their right to occupy and settle western lands.

T he first step, restricting rights of the colonists, was followed by a series of others, which finally brought the growing tension to the revolution.

he first step, restricting rights of the colonists, was followed by a series of others, which finally brought the growing tension to the revolution.

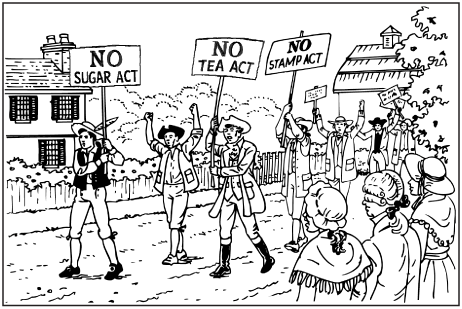

Taxation without Representation

The end of the war was marked with big problems for the British Government — Britain had an immense war debt and needed more money to support the growing empire. New British King George III and his ministers were determined to take this money from the colonies. Beginning from 1764, British Parliament passed a number of acts which restricted colonial trade and levied new duties on imported goods.

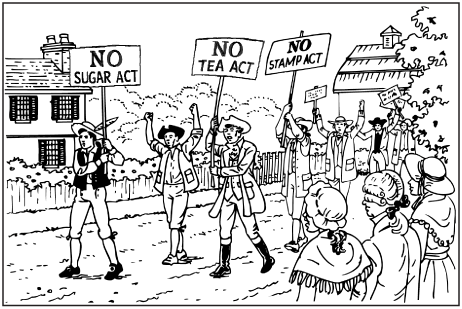

The first was the Sugar Act of 1764, it forbade the importation of foreign rum and levied duties on wines, silks, coffee and some other luxury items. It was followed by the Currency Act, which outlawed colonial paper money. Both documents hampered developing American economy, gave way to smuggling, and threatened commerce.

Colonial governments tried to protest against the Acts, but as they were disunited, their separate petitions to the British Government had no effect.

Next step made by the British Government was the Stamp Act requiring tax stamps on most printed materials. It affected all people who did any kind of business and, more important, it broke with colonial tradition of self-imposed taxation.

The Stamp Act arose hostility in all layers of society, but the biggest resistance was shown by leading merchants, journalists, lawyers and clergymen. Very soon the resistance grew to a secret intercolonial association, "the Sons of Liberty" aiming to protest the Stamp Act.

In the fall and winter of 1765 and 1766. the Stamp Act was protested on three separate fronts — by the Sons of Liberty, who held mass meetings, by the colonial legislatures, who petitioned Parliament to repeal "taxation without representation" and, finally, American merchants organized nonimportation associations to put economic pressure on British exporters.

Due to mass resistance in colonies and in London (British exporters were also affected by the crisis), Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766. But the issue of "taxation without representation" had already become central in the life of the colonies. The colonies viewed the British Parliament as having no right to pass laws for the colonies because colonies were not represented in Parliament, and no colonial legislature had the right to pass laws for England.

In 1767, colonists were struck by a new series of taxes on trade goods like paper, glass, and tea imposed according to the Townshend Acts (by the name of British Head of Ministry). These acts aimed to support colonial governors, officers and the British army in America. New customs provoked further growth of violence in colonies, as colonial imports from England dropped dramatically, especially in New York, New England, and Pennsylvania. Many colonists had to dress in homespun clothing and look for substitutes for tea. They used homemade paper and their houses went unpainted.

Bostonians especially hated the new tax, so two British regiment? were dispatched there to protect customs officers- Presence of British soldiers provoked Bostonians' patience — guards checked all travelers and their goods, and paraded over the city streets to show British power. On March 5, 1770, the resistance grew into violence — a crowd of Bostonians began to snowball British sentries, who, in their turn, opened fire on the crowd. In the accident, later called the "Boston Massacre", four Bostonians were killed and some wounded. It was widely discussed as an example of British tyranny in colonies.

Fierce colonial opposition made in 1770 British Parliament repealed all the Townshend duties except a duty on tea, and the campaign against England was losing its force.

American Revolution

The 1770s witnessed the first dramatic experience and one of the major conflicts ever fought on American soil. The Revolution was much more than fighting between British army and colonial militiamen — it destroyed colonial structure and economy, uprooted thousands of civilian families and finally united the colonies into a whole.

In July 1776, the thirteen colonies had, out of desperation, to declare independence and join together into a confederation of states, but it took years of further fighting to cease hostility and to begin to accept each other as fellow citizens. The Revolution not only led Americans to develop new conceptions of politics, but also gave northerners and southerners the first real chance to learn what they had in common, and to favor centralization of power at the national level.

T he Boston Tea Party and the First Continental Congress

he Boston Tea Party and the First Continental Congress

By 1773, all the Townshend duties were abolished, only the tax on tea was still in effect. It deprived thousands of colonists of their favorite drink that was an important component of Anglo-American life and traditions. But still it was an only heavily dutied product, so many were reducing the protests and only few radicals as Samuel Adams with his supporters continued protesting. The other reason for keeping order was that illegal trade was flourishing, and most tea in the colonies was of foreign origin, imported illegally by smugglers.

In May 1773, British Parliament gave the right to sell tea in colonies to the East India Company — that decision made any other selling of tea unprofitable, and what Samuel Adams considered even more dangerous — it could make many colonists to admit Parliament's right to tax them and to establish an East India Company monopoly of all colonial trade.

The first ships with tea were perceived as a new threat to colonial freedom, so four major American cities protested against them — in New York City the ships failed to arrive on schedule, in Philadelphia citizens persuaded the captain to sail back to England. The only confrontation occurred in Boston, where a new crisis called the Boston Tea Party started. The royal governor did not want to send the tea back to England, so at night Bostonian radicals led by Samuel Adams boarded three ships with tea, as Indians, and dumped the cargo into the harbor; they were mainly representatives of Bostonian white citizens, who opposed British taxation.

The result of the Tea Party was expressed by British Parliament in such punitive measures as the "Coersive Acts" that prevented Bostonians from having access to the sea and banned town meetings and the "Quebec Ac!" that granted religious freedom to Catholics and thus alarmed the Protestant colonists. For colonial radicals the Acts, which were already collectively called the "Intolerable Acts" proved that Britain had made a new plan to oppress them. So the colonies agreed to send their delegates to Philadelphia in September 1774.

The first meeting of colonial delegates hosted 55 representatives from each colony except Georgia and became known as the First Continental Congress. The congressmen had three important tasks to accomplish — to define American grievances, to develop a plan for resistance, and, finally, to outline a theory of their constitutional relationship with Britain. The delegates agreed on the list of laws that had to be repealed, chose boycott as their method of economic resistance, but could not reach a consensus on constitutional relationship. Finally they ended with a resolution that all the colonists had the right to "life, liberty and property", and that provincial legislatures could set "taxation and internal polity". The most radical colonists declared that colonies owed allegiance only to British King George III, but legitimate authority had to be exercises by colonial assemblies, which had historically governed them.

Now the colonists were divided into those, who called for action — "the Colonies must either submit or triumph" — and the Loyalists, who had no intention to be independent from Britain.

War Begins

The war between the colonists and British troops began with battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775. In Lexington British soldiers fired at a band of 70 Minutemen (colonial militia), who gathered to express their protest. In Concord, where the contingents of militia were larger, British troops (colonists called them "redcoats") suffered greater losses — colonial militiamen were attacking them from behind the trees, bushes, and houses along the road.

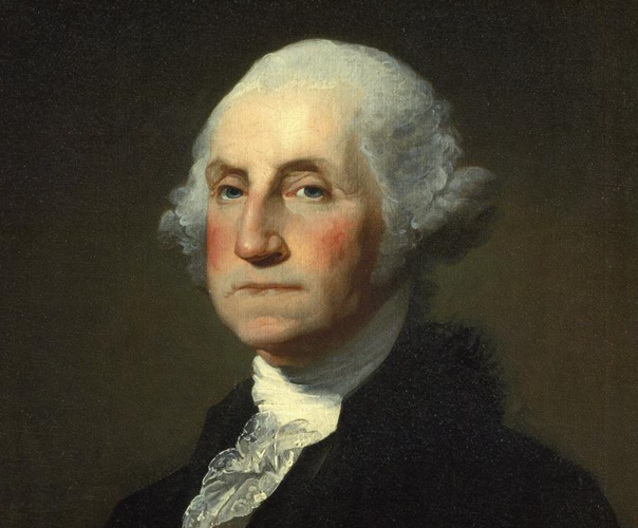

These battles marked the beginning of American War for Independence, which was supported by the delegates of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia in May, 1775. Congressmen voted for war, authorized the printing of money to purchase necessary goods, established a committee to supervize relations with foreign countries, and took steps to strengthen the militia. Also the most important task was accomplished — the Continental Army was created and Colonel George Washington of Virginia was appointed its commander-in-chief,

The leaders of the Revolution had three important tasks to accomplish:

— to persuade colonists to take side of the patriot fighters for American independence;

— to get international recognition and the assistance of France, which was crucial to the winning of independence;

— to try not to lose battles with the British army decisively. George Washington — commander-in-chief of the American army, quickly realized that American success will be much a result of their endurance than of superiority.

The British, in their turn, were sure that American army would not be able to fight with the trained British soldiers, so the campaign of 1776 would be the first and the last of the war. The British also tended to compare this war with what they had fought successfully in Europe, so they adopted the same strategy of capturing major American cities.

But British strategy proved false — American population was dispersed, and only 5'% of colonists lived in the major cities. Capturing of these cities did not mean immediate victory, and, moreover, military victory did not mean political victory. The British could not realize that it was not a convential European war; it was a new kind of conflict — the first modern war of national liberation.

D eclaration of Independence

eclaration of Independence

Long months after fighting with Britain had begun, American leaders did not try to break with the empire. The decisive step to independence was made by Thomas Paine, who published a pamphlet "Common Sense" in January 1776. In his work Paine criticized common American assumptions about government and the colonies' relationship to England. He proved that the establishing of a republic was necessary, democracy was the only way to preserve freedom, and rejected the balance of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. Paine insisted that Britain was exploiting the colonies unmercifully and rejected the assertion that an independent America would be weak and divided — he proved that America's strength would grow when freed from European control.

The pamphlet got enormous popularity, converting many colonists to independence — by late spring 1776 it was inevitable. On May 10,1776, the Second Continental Congress adopted a resolution calling for separation, and in June a committee of five, headed by Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, was appointed to prepare a formal declaration.

The Declaration became mainly Jefferson's work, who was a Virginian lawyer educated at the college of William and Mary. Declaration of Independence was based on English Enlightment political philosophy, particularly on John Locke's "Second Treatise in Government", where traditional rights of Englishmen were universalized into the natural rights of all humankind.

The draft of Declaration was laid before Congress on June 28; congressmen debated the wording for some more days, and adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4. The delegates knew that they were committing treason. Now they had to win the war otherwise they would have been executed. As Benjamin Franklin put it, "We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately". The real struggle still lay before them.

Cultural Note: Signing the Declaration of Independence

A lthough the Declaration of Independence was adopted and printed on July 4, it was immediately signed only by the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock, and its secretary, Charles Thomson. Hancock boldly put his big signature noting: "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"

lthough the Declaration of Independence was adopted and printed on July 4, it was immediately signed only by the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock, and its secretary, Charles Thomson. Hancock boldly put his big signature noting: "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"

Most of the other delegates signed the Declaration on August 2 ceremony, and one of the delegates, Thomas McKean of Delaware signed it only in 1781. Signers were so afraid of their fate that the names of those who signed the Declaration weren't made public until 1777.

The name of John Hancock, however, survived not only in history, but also can be often heard in the popular expression "Put you Hancock here", used to ask people to sign the documents.

Fighting for Independence

After the Declaration of Independence was adapted, American army had to defend it. It was clear that fighting would not be an easy one — British redcoats were well-equipped, Britain had the strongest navy in the world and enough money to hire soldiers to fight against the rebellious patriots. Also there were many British sympathizers on American soil — the loyalists, among whom were people of different backgrounds:

— recent British immigrants (English, Scots and Irish), who remained closely identified with their mother country. They were mostly concentrated in New York, Georgia, and the backcountry of North and South Carolina. In 1776, the number of loyalists in these places was up to 40 % of colonial population;

— German, Dutch, and French religious congregations in colonies, who doubted that their religious beliefs would be safe in an independent nation dominated by Anglo- Americans;

— Canada's French Catholics, who bad been guaranteed religious freedom by the British and worried that their privileges would disappear. They made the biggest group of Britain's supporters in North America;

— Indians along the frontier, who were afraid of further Anglo-American expansion;

— African-American slaves, who believed that the British would free them because parliament had never explicitly established slavery.

All these categories constituted an important support for British redcoats in the coming war.

On the side of Americans were militiamen and hired Continental soldiers. Most Americans served a short term, they were worse equipped and only a support of French allies helped colonial army to win the war.

The first decisive battle after the Declaration of Independence began in late June 1776 for New York. Washington's army was finally defeated by the British troops led by General William Howe. By November, Howe had captured Fort Washington on Manhattan Island, so New York City remained under British control until the end of the war.

After losing New York General Washington led his men in retreat across New Jersey. It allowed British troops to follow them and soon redcoats controlled most of New Jersey. The colonists on the occupied territories began losing faith in Washington's army — cold winter and British confidence changed many minds. "These are the times that try men's souls," wrote Thomas Paine in his next pamphlet "The Crisis". "The Summer soldiers and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; ...yet we have this consolidation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph".

Paine's prophesy proved right — the next two battles at Trenton and Princeton finished in American's favor, they also regained most of the territory occupied by the British.

1777 proved to be the turning point in that war. At the beginning of the year General Howe with his troops defeated Americans in Pennsylvania, occupied Philadelphia and forced the Continental Congress to flee. American army again had to spend winter lacking food, clothing and supplies. But still it was a very important period for Americans because they managed to ally with the French.

This important task was accomplished by Benjamin Franklin, who negotiated and won French assistance. The French supported Americans for many reasons — they wanted to restore the balance of power seriously weakened by the French and Indian War (The Seven Years War), their geopolitical interests in North America had been threatened by the British and they wanted to support the war against their oldest enemy.

In February 1778, France signed two treaties with Americans, by which she recognized American independence and provided assistance for rebellious nation until the war was won. This alliance was of great benefit for the patriots — France began to help the Americans openly, sending troops, supplies and naval vessels. The British could no longer focus their attention on the colonies alone as now they had to fight the French in the West Indies and other places. In 1779, Spain entered the war as an ally of France (not the United States) to magnify Britain's problems. Throughout the war French assistance was of great importance to Americans.

After the French had been involved into the war, the British moved south, as there were many loyalists, who could support the redcoats. In

late 1778, they captured Savannah, Georgia and moved to Charleston, the principal southern port. On May 1779, General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered the city — it was the greatest American defeat of the war.

But that loss seemed to have no effect on American troops — they continued attack British supply lines and confront British forces. The most significant battle took place at Cowpens, South Carolina, in early 1781, where Americans defeated the British and made them retreat to Virginia.

The French, who took part in the war, prevented the British from getting supplies, harassed British ships and, finally, defeated the British troops at Yorktown near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay in October, 1781.

This was not a victory to immediately end war, but a new British Government soon decided to start peace negotiations. They took place in Paris in early 1782; American side was represented by Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay. The formal treaty known as the Treaty of Paris was signed by the British and American representatives on September 3, 1783.

The treaty recognized the boundaries of a new nation, returned Florida to Spain and acknowledged the independence, freedom and sovereignty of the 13 former colonies. The long war was over, now the new task of uniting the nation was set.

FORMING A REPUBLIC

Fighting for independence changed the life in the New World almost entirely — during the war Americans reshaped their political structures, their intellectual world, and their social interactions. The root of all changes was an idea to create a new society and a new republican government based wholly on the consent of the people.

By the end of the war, Americans had abandoned British idea of balanced monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy — now they believed in a state where people could rule. The most difficult question was, however, how to define "the people" — almost all white men agreed that women and black should be excluded from politics.

There were also many other questions to answer — the structure of people's government and its forms, the number of voters, and how often the representatives of people will meet. Americans replied to these questions in different ways. Opinions also differed in other important matters — about dealing with Indian tribes, constructing foreign policy, and, the most difficult, what to do with slaves, if "all men are created equal" according to the Declaration of Independence.

Many people saw the new republic as a unique type of government, which could be built only by especially virtuous people — very soon this idea became crucial for American life and shaped American culture for many years. After 1776, American literature, theater, art, and architecture all had moral goals — they intended to inspire audience to behave virtuously.

For the first time special attention was also given to American women — they were not looked upon as perspective voters, but as mothers of the republic's children, they played a very important role in their upbringing. This brought republican leaders to the conclusion that mothers of the rising generation had to be properly educated.

C reating National Government and Constitution

reating National Government and Constitution

In May 1776, two months before the Declaration of Independence was passed, the Second Continental Congress directed the colonies to form new governments. They were to be based on principles of self-government exercised by colonies long before the Revolution. Between January 1779 and April 1777, ten of the thirteen new states adopted their own constitutions based on colonial experience, English practice, and new ideas of republicanism and democracy. All the constitutions were ratified by people, who theoretically were sovereigns in the republic. Most states had governors elected by the state legislatures. The state legislatures, in their turn, were elected by popular vote.

All state constitutions attempted to establish good governments by balancing the powers of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches against one another, to limit the number of terms officials could serve and make meetings of governing assemblies open to public. The process of forging final variants of state constitution was open to debate, almost everywhere it lasted for the next 10 years.

Meanwhile the USA was governed according to the compact that bound the states together as a nation. This compact — "The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union" — was signed in July 1778 and ratified in March 1781. The Articles of Confederation soon appeared to have many drawbacks — they set up a federal government with very limited powers. National government lacked authority to regulate taxes and trade, to control foreign affairs and western lands.

The Continental Congress (after 1781 its name was changed to the Confederation Congress) was too inefficient to govern effectively — there was no proper distribution of power, no independent income and no authority to compel the states to accept the ruling of the Congress.

Politically and economically, the new nation was close to chaos. The Articles of Confederation had to be revised because weak central government threatened the existence of the entire USA.

In May 1787, the Confederation Congress gathered in Philadelphia to revise the articles. The 55 delegates of all states but Rhode Island included most of the outstanding leaders, or Founding Fathers, of the nation. They represented a wide range of interests, backgrounds, and stations in life and their primary aim was to provide a constitution which could create a strong government for diverse society, and to make this government directly responsive to the will of the people.

The US Constitution

The key to the Constitution was the distribution of political authority between three separate branches — legislative, judicial, and executive, each branch with distinct powers to balance the other two branches. The legislative branch — like the British Parliament was divided between two houses — the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Each state was concerned with a number of representatives in Congress — the larger states wanted proportional representation while the smaller states insisted on equal representation for all states. The problem was settled by the "Great Compromise" — every state got equal representation in the Senate (two seats), and proportional representation in the House of Representatives (according to the number of citizens).

Proportional representation caused further discussions and clashes — delegates from the states where the number of slaves was larger wanted all people, black and white, to be counted equally; delegates from states with few slaves wanted only free people to be counted. The issue was resolved by the "three-fifths compromise", which was patterned by the formula of taxation developed by the Confederation Congress in 1783 — only 60 % of all slaves were counted for representation. The tree-fifths compromise was a part of the Great Compromise.

The Great Compromise became the first step in balancing political decisions for the nation, which had a wide range of opinions. The draft of the Constitution was based on the principle of checks and balances — the main principle advocated by James Madison — the Father of the Constitution.

The government, he believed, had to be constructed in such a way that it could not become tyrannical or fall wholly under the influence of a particular interest group. The Declaration of Independence was also an important guide, as it fixed the ideas of self-government and preservation of human rights; besides, the authors of the Constitution were influenced by the works of such European philosophers as Montesquieu and John Locke.

The process of making a draft of the Constitution went on till September 1787, when 39 of the present delegates signed it. Probably none of them was fully satisfied. "I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve" admitted Benjamin Franklin, "but I am not sure I shall never approve them".

To come into action the Constitution had to be ratified by at least nine states. The first states to ratify the Constitution were Delaware, New Jersey, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Connecticut, but the other states insisted on important additions. These were 10 amendments guaranteeing such fundamental rights as freedom of religion, speech, press, and assembly trial by jury, prohibition of unreasonable searches or arrests. These amendments, known as the Bill of Rights, were incorporated into the Constitution in 1791.

That variant of the Constitution proved to be so efficient that American Constitution successfully serves for more than 200 years with only 27 amendments. It is the world's oldest written constitution in force, and it has served as the model for a number of constitutions all over the world. American Constitution has two important features — it is simple and flexible, so it can guide the evolution of governmental institutions and provide the basis for political stability, individual freedom, economic growth and social progress.

B uilding a Government. The First Political Parties

uilding a Government. The First Political Parties

The process of organizing the government began after the Constitution was ratified by Virginia and New York. In 1788, Congress fixed the city of New York as the seat of new government (in 1790 the capital of the nation was moved to Philadelphia, and in 1800 to Washington, D.C.)

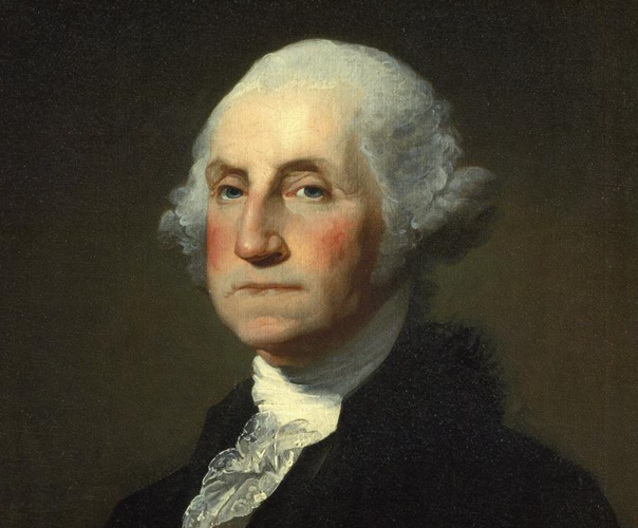

After the Constitution was ratified, George Washington was unanimously chosen President in April, 1789, John Adams of Massachusetts — the Vice President. On April 30, 1789, George Washington promised to "preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States" to the best of his ability. With these words he was "inaugurated" as the first President of the United States. Now the new government had to create state machinery.

Congress quickly approved the creation of the departments of State and Treasury, established the federal judiciary, Supreme Court and district courts, and appointed a secretary of war and an attorney general. George Washington also created the presidential Cabinet to consult the President in making important decisions.

Washington worked cautiously, understanding that he was setting precedents for the future. When the question of his title arose a hot debate (Vice President John Adams proposed "His Highness, the President of the United States of America, and Protector of their Liberties"), Washington said nothing, but soon the accepted title became a plain "Mr. President".

Washington also appointed people to head the executive departments and developed policies for settling new territories. During his presidency the first political parties appeared in the USA.

The conflict between these two political parties — the Federalists and Antifederalists had a profound impact on American history. The Federalists were led by Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury Department. They represented the interests of town merchants, seeing the future of the United States in great cities and important industries.

The Antifederalists, led by Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State, advocated the interests of rural and southern regions. They saw the country's future in small communities and farms, as a decentralized agrarian republic.

Hamilton, who sought a strong central government, acted for industrial development and commercial activity. He devised a Bank of the United States, modelled on the Bank of England. The bank had the right to bring into circulation national currency, and lend money, encouraging commerce and industry.

Jefferson wanted a less strong central government political power at the local level. The government that governs least, Jefferson argued governs best.

These two powerful political leaders and their parties presented the division in the Cabinet of the first President, and only Washington's strength and prestige kept these parties from warring with one another openly — but they did so privately and in the newspapers.

The clashes between two political parties in America could not spoil a positive effect of developing two-party system — they influenced American political thought and established a solid ground for effective government.

Focus on Government

As the USA is a democratic republic, its government is a government of people and their representatives (elected officials). It is called the federal government because the nation is a federation or association of states. The US Constitution gives the federal government only limited powers, all other powers belong to individual states.

The three branches of government (legislative, executive and judicial) provide a system of checks and balances, when one branch has some control over the other two branches.

Congress represents the legislative branch of the US government. It consists of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The responsibility of the Congress is to propose and pass laws. In the system of checks and balances, Congress can refuse to approve Presidential appointments and can override a Presidential veto.

The executive branch consists of the President, the Vice President, the Cabinet and the thirteen departments, and the independent agencies. The responsibility of this branch is to enforce laws. The President has the power to veto any bill of Congress. The President also appoints all Supreme Court Justices.

The judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court, eleven Circuit Courts of Appeals, and ninety-four District Courts. This branch explains and interprets laws and makes decisions in lawsuits. It has power over the two other branches because it can declare their laws and actions unconstitutional.

References:

Overview of American History. Л.Галицина, «Школьный свет»

http://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/ruwiki/1525624

https://talonsgalen.edublogs.org/

http://supremeboundlessway.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/declaration_independence1.jpg

http://www.americaslibrary.gov/assets/jb/revolut/jb_revolut_subj_e.jpg

http://fr.academic.ru/pictures/frwiki/89/Yorktown80.JPG

http://greatprovince.com/uploads/Boston_Tea_Party_Currier_colored2.jpg

http://theblackcommenter.files.wordpress.com/2009/08/foundingfathers.jpg

http://images-cdn.lancasteronline.com/356768_640.jpg

he French and Indian War

he French and Indian War he first step, restricting rights of the colonists, was followed by a series of others, which finally brought the growing tension to the revolution.

he first step, restricting rights of the colonists, was followed by a series of others, which finally brought the growing tension to the revolution. he Boston Tea Party and the First Continental Congress

he Boston Tea Party and the First Continental Congress eclaration of Independence

eclaration of Independence lthough the Declaration of Independence was adopted and printed on July 4, it was immediately signed only by the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock, and its secretary, Charles Thomson. Hancock boldly put his big signature noting: "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"

lthough the Declaration of Independence was adopted and printed on July 4, it was immediately signed only by the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock, and its secretary, Charles Thomson. Hancock boldly put his big signature noting: "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!" reating National Government and Constitution

reating National Government and Constitution uilding a Government. The First Political Parties

uilding a Government. The First Political Parties