Roman Empire

Arts[edit] Main article: Roman art

The Aldobrandini Wedding, 27 BC – 14 AD

The Wedding of Zephyrus and Chloris (54–68 AD, Pompeian Fourth Style) within painted architectural panels from the Casa del Naviglio

People visiting or living in Rome or the cities throughout the Empire would have seen art in a range of styles and media on a daily basis. Public or official art — including sculpture, monuments such as victory columns or triumphal arches, and the iconography on coins — is often analysed for its historical significance or as an expression of imperial ideology.[470][471] At Imperial public baths, a person of humble means could view wall paintings, mosaics, statues, and interior decoration often of high quality.[472] In the private sphere, objects made for religious dedications, funerary commemoration, domestic use, and commerce can show varying degrees of esthetic quality and artistic skill.[473] A wealthy person might advertise his appreciation of culture through painting, sculpture, and decorative arts at his home—though some efforts strike modern viewers and some ancient connoisseurs as strenuous rather than tasteful.[474] Greek art had a profound influence on the Roman tradition, and some of the most famous examples of Greek statues are known only from Roman Imperial versions and the occasional description in a Greek or Latin literary source.[475]

Despite the high value placed on works of art, even famous artists were of low social status among the Greeks and Romans, who regarded artists, artisans, and craftsmen alike as manual labourers. At the same time, the level of skill required to produce quality work was recognized, and even considered a divine gift.[476]

Portraiture

[edit] Main article: Roman portraiture

Two portraits circa 130 AD: the empress Vibia Sabina (left); and the Antinous Mondragone, one of the abundant likenesses of Hadrian's famously beautiful male companion Antinous

Portraiture, which survives mainly in the medium of sculpture, was the most copious form of imperial art. Portraits during the Augustan period utilize youthful and classical proportions, evolving later into a mixture of realism and idealism.[477] Republican portraits had been characterized by a "warts and all" verism, but as early as the 2nd century BC, the Greek convention of heroic nudity was adopted sometimes for portraying conquering generals.[478] Imperial portrait sculptures may model the head as mature, even craggy, atop a nude or seminude body that is smooth and youthful with perfect musculature; a portrait head might even be added to a body created for another purpose.[479] Clothed in the toga or military regalia, the body communicates rank or sphere of activity, not the characteristics of the individual.[480]

Women of the emperor's family were often depicted dressed as goddesses or divine personifications such as Pax ("Peace"). Portraiture in painting is represented primarily by the Fayum mummy portraits, which evoke Egyptian and Roman traditions of commemorating the dead with the realistic painting techniques of the Empire. Marble portrait sculpture would have been painted, and while traces of paint have only rarely survived the centuries, the Fayum portraits indicate why ancient literary sources marvelled at how lifelike artistic representations could be.[481]

Sculpture

[edit] Main article: Roman sculpture

The bronze Drunken Satyr, excavated at Herculaneum and exhibited in the 18th century, inspired an interest among later sculptors in similar "carefree" subjects.[482]

Examples of Roman sculpture survive abundantly, though often in damaged or fragmentary condition, including freestanding statues and statuettes in marble, bronze and terracotta, and reliefs from public buildings, temples, and monuments such as the Ara Pacis, Trajan's Column, and the Arch of Titus. Niches in amphitheatres such as the Colosseum were originally filled with statues,[483][484] and no formal garden was complete without statuary.[485]

Temples housed the cult images of deities, often by famed sculptors.[486] The religiosity of the Romans encouraged the production of decorated altars, small representations of deities for the household shrine or votive offerings, and other pieces for dedicating at temples.

Sarcophagi

[edit] Main article: Ancient Roman sarcophagi

On the Ludovisi sarcophagus, an example of the battle scenes favoured during the Crisis of the Third Century, the "writhing and highly emotive" Romans and Goths fill the surface in a packed, anti-classical composition[487]

Elaborately carved marble and limestone sarcophagi are characteristic of the 2nd to the 4th centuries[488] with at least 10,000 examples surviving.[489] Although mythological scenes have been most widely studied,[490] sarcophagus relief has been called the "richest single source of Roman iconography,"[491] and may also depict the deceased's occupation or life course, military scenes, and other subject matter. The same workshops produced sarcophagi with Jewish or Christian imagery.[492]

Painting

[edit]

The Primavera of Stabiae, perhaps the goddess Flora

Romans absorbed their initial paint models and techniques in part from Etruscan painting and in part from Greek painting.

Examples of Roman paintings can be found in a few palaces (mostly found in Rome and surroundings), in many catacombs and in some villas such as the villa of Livia.

Much of what is known of Roman painting is based on the interior decoration of private homes, particularly as preserved at Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. In addition to decorative borders and panels with geometric or vegetative motifs, wall painting depicts scenes from mythology and the theatre, landscapes and gardens, recreation and spectacles, work and everyday life, and erotic art.

A unique source for Jewish figurative painting under the Empire is the Dura-Europos synagogue, dubbed "the Pompeii of the Syrian Desert,"[n 18] buried and preserved in the mid-3rd century after the city was destroyed by Persians.[493][494]

Mosaic

[edit] Main article: Roman mosaic

The Triumph of Neptune floor mosaic from Africa Proconsularis (present-day Tunisia), celebrating agricultural success with allegories of the Seasons, vegetation, workers and animals viewable from multiple perspectives in the room (latter 2nd century)[495]

Mosaics are among the most enduring of Roman decorative arts, and are found on the surfaces of floors and other architectural features such as walls, vaulted ceilings, and columns. The most common form is the tessellated mosaic, formed from uniform pieces (tesserae) of materials such as stone and glass.[496] Mosaics were usually crafted on site, but sometimes assembled and shipped as ready-made panels. A mosaic workshop was led by the master artist (pictor) who worked with two grades of assistants.[497]

Figurative mosaics share many themes with painting, and in some cases portray subject matter in almost identical compositions. Although geometric patterns and mythological scenes occur throughout the Empire, regional preferences also find expression. In North Africa, a particularly rich source of mosaics, homeowners often chose scenes of life on their estates, hunting, agriculture, and local wildlife.[495] Plentiful and major examples of Roman mosaics come also from present-day Turkey, Italy, southern France, Spain, and Portugal. More than 300 Antioch mosaics from the 3rd century are known.[498]

Opus sectile is a related technique in which flat stone, usually coloured marble, is cut precisely into shapes from which geometric or figurative patterns are formed. This more difficult technique was highly prized and became especially popular for luxury surfaces in the 4th century, an abundant example of which is the Basilica of Junius Bassus.[499]

Decorative arts

[edit] See also: Ancient Roman pottery and Roman glass

Decorative arts for luxury consumers included fine pottery, silver and bronze vessels and implements, and glassware. The manufacture of pottery in a wide range of quality was important to trade and employment, as were the glass and metalworking industries. Imports stimulated new regional centres of production. Southern Gaul became a leading producer of the finer red-gloss pottery (terra sigillata) that was a major item of trade in 1st-century Europe.[500] Glassblowing was regarded by the Romans as originating in Syria in the 1st century BC, and by the 3rd century, Egypt and the Rhineland had become noted for fine glass.[501][502]

Silver cup, from the Boscoreale Treasure (early 1st century AD)

Finely decorated Gallo-Roman terra sigillata bowl

Gold earrings with gemstones, 3rd century

Glass cage cup from the Rhineland, 4th century

Performing arts

[edit] Main articles: Theatre of ancient Rome and Music of ancient Rome

Actor dressed as a king and two muses. Fresco from Herculaneum, 30–40 AD

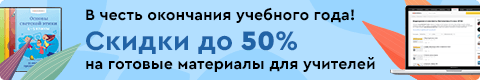

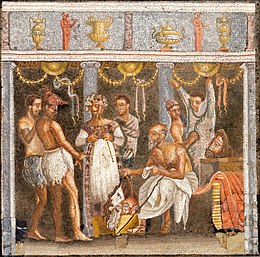

In Roman tradition, borrowed from the Greeks, literary theatre was performed by all-male troupes that used face masks with exaggerated facial expressions that allowed audiences to "see" how a character was feeling. Such masks were occasionally also specific to a particular role, and an actor could then play multiple roles merely by switching masks. Female roles were played by men in drag (travesti). Roman literary theatre tradition is particularly well represented in Latin literature by the tragedies of Seneca. The circumstances under which Seneca's tragedies were performed are however unclear; scholarly conjectures range from minimally staged readings to full production pageants. More popular than literary theatre was the genre-defying mimus theatre, which featured scripted scenarios with free improvization, risqué language and jokes, sex scenes, action sequences, and political satire, along with dance numbers, juggling, acrobatics, tightrope walking, striptease, and dancing bears.[503][504][505] Unlike literary theatre, mimus was played without masks, and encouraged stylistic realism in acting. Female roles were performed by women, not by men.[506] Mimus was related to the genre called pantomimus, an early form of story ballet that contained no spoken dialogue. Pantomimus combined expressive dancing, instrumental music and a sung libretto, often mythological, that could be either tragic or comic.[507][508]

All-male theatrical troupe preparing for a masked performance, on a mosaic from the House of the Tragic Poet

Although sometimes regarded as foreign elements in Roman culture, music and dance had existed in Rome from earliest times.[509] Music was customary at funerals, and the tibia (Greek aulos), a woodwind instrument, was played at sacrifices to ward off ill influences.[510] Song (carmen) was an integral part of almost every social occasion. The Secular Ode of Horace, commissioned by Augustus, was performed publicly in 17 BC by a mixed children's choir. Music was thought to reflect the orderliness of the cosmos, and was associated particularly with mathematics and knowledge.[511]

Various woodwinds and "brass" instruments were played, as were stringed instruments such as the cithara, and percussion.[510] The cornu, a long tubular metal wind instrument that curved around the musician's body, was used for military signals and on parade.[510] These instruments are found in parts of the Empire where they did not originate and indicate that music was among the aspects of Roman culture that spread throughout the provinces. Instruments are widely depicted in Roman art.[512]

The hydraulic pipe organ (hydraulis) was "one of the most significant technical and musical achievements of antiquity", and accompanied gladiator games and events in the amphitheatre, as well as stage performances. It was among the instruments that the emperor Nero played.[510]

Although certain forms of dance were disapproved of at times as non-Roman or unmanly, dancing was embedded in religious rituals of archaic Rome, such as those of the dancing armed Salian priests and of the Arval Brothers, priesthoods which underwent a revival during the Principate.[513] Ecstatic dancing was a feature of the international mystery religions, particularly the cult of Cybele as practiced by her eunuch priests the Galli[514] and of Isis. In the secular realm, dancing girls from Syria and Cadiz were extremely popular.[515]

Like gladiators, entertainers were infames in the eyes of the law, little better than slaves even if they were technically free. "Stars", however, could enjoy considerable wealth and celebrity, and mingled socially and often sexually with the upper classes, including emperors.[516] Performers supported each other by forming guilds, and several memorials for members of the theatre community survive.[517] Theatre and dance were often condemned by Christian polemicists in the later Empire,[509] and Christians who integrated dance traditions and music into their worship practices were regarded by the Church Fathers as shockingly "pagan."[518] St. Augustine is supposed to have said that bringing clowns, actors, and dancers into a house was like inviting in a gang of unclean spirits.[519][520]