Roman Empire

Languages[edit] |

| This section may contain misleading parts. Please help clarify this article according to any suggestions provided on the talk page. (September 2016) |

Main article: Languages of the Roman Empire

The language of the Romans was Latin, which Virgil emphasized as a source of Roman unity and tradition.[56][57][58] Until the time of Alexander Severus (reigned 222–235), the birth certificates and wills of Roman citizens had to be written in Latin.[59] Latin was the language of the law courts in the West and of the military throughout the Empire,[60] but was not imposed officially on peoples brought under Roman rule.[61][62] This policy contrasts with that of Alexander the Great, who aimed to impose Greek throughout his empire as the official language.[63] As a consequence of Alexander's conquests, Koine Greek had become the shared language around the eastern Mediterranean and into Asia Minor.[64][65] The "linguistic frontier" dividing the Latin West and the Greek East passed through the Balkan peninsula.[66]

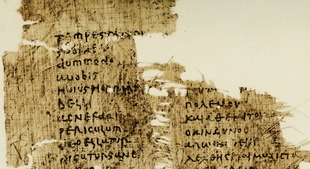

A 5th-century papyrus showing a parallel Latin-Greek text of a speech by Cicero[67]

Romans who received an elite education studied Greek as a literary language, and most men of the governing classes could speak Greek.[68] The Julio-Claudian emperors encouraged high standards of correct Latin (Latinitas), a linguistic movement identified in modern terms as Classical Latin, and favoured Latin for conducting official business.[69] Claudius tried to limit the use of Greek, and on occasion revoked the citizenship of those who lacked Latin, but even in the Senate he drew on his own bilingualism in communicating with Greek-speaking ambassadors.[69] Suetonius quotes him as referring to "our two languages".[70]

In the Eastern empire, laws and official documents were regularly translated into Greek from Latin.[71] The everyday interpenetration of the two languages is indicated by bilingual inscriptions, which sometimes even switch back and forth between Greek and Latin.[72][73] After all freeborn inhabitants of the empire were universally enfranchised in 212 AD, a great number of Roman citizens would have lacked Latin, though Latin remained a marker of "Romanness."[74]

Among other reforms, the emperor Diocletian (reigned 284–305) sought to renew the authority of Latin, and the Greek expression hē kratousa dialektos attests to the continuing status of Latin as "the language of power."[75] In the early 6th century, the emperor Justinian engaged in a quixotic effort to reassert the status of Latin as the language of law, even though in his time Latin no longer held any currency as a living language in the East.[76]

Local languages and linguistic legacy

[edit]

Bilingual Latin-Punic inscription at the theatre in Leptis Magna, Roman Africa (present-day Libya)

References to interpreters indicate the continuing use of local languages other than Greek and Latin, particularly in Egypt, where Coptic predominated, and in military settings along the Rhine and Danube. Roman jurists also show a concern for local languages such as Punic, Gaulish, and Aramaic in assuring the correct understanding and application of laws and oaths.[77] In the province of Africa, Libyco-Berber and Punic were used in inscriptions and for legends on coins during the time of Tiberius (1st century AD). Libyco-Berber and Punic inscriptions appear on public buildings into the 2nd century, some bilingual with Latin.[78] In Syria, Palmyrene soldiers even used their dialect of Aramaic for inscriptions, in a striking exception to the rule that Latin was the language of the military.[79]

The Babatha Archive is a suggestive example of multilingualism in the Empire. These papyri, named for a Jewish woman in the province of Arabia and dating from 93 to 132 AD, mostly employ Aramaic, the local language, written in Greek characters with Semitic and Latin influences; a petition to the Roman governor, however, was written in Greek.[80]

The dominance of Latin among the literate elite may obscure the continuity of spoken languages, since all cultures within the Roman Empire were predominantly oral.[78] In the West, Latin, referred to in its spoken form as Vulgar Latin, gradually replaced Celtic and Italic languages that were related to it by a shared Indo-European origin. Commonalities in syntax and vocabulary facilitated the adoption of Latin.[81][82][83]

After the decentralization of political power in late antiquity, Latin developed locally into branches that became the Romance languages, such as Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Catalan and Romanian, and a large number of minor languages and dialects. Today, more than 900 million people are native speakers worldwide.[84]

As an international language of learning and literature, Latin itself continued as an active medium of expression for diplomacy and for intellectual developments identified with Renaissance humanism up to the 17th century, and for law and the Roman Catholic Church to the present.[85][86]

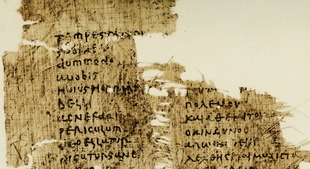

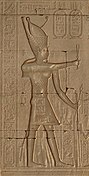

"Gate of Domitian and Trajan" at the northern entrance of the Temple of Hathor, and Roman emperor Domitian as Pharaoh of Egypt on the same gate, together with Egyptian hieroglyphs. Dendera, Egypt.[87][88]

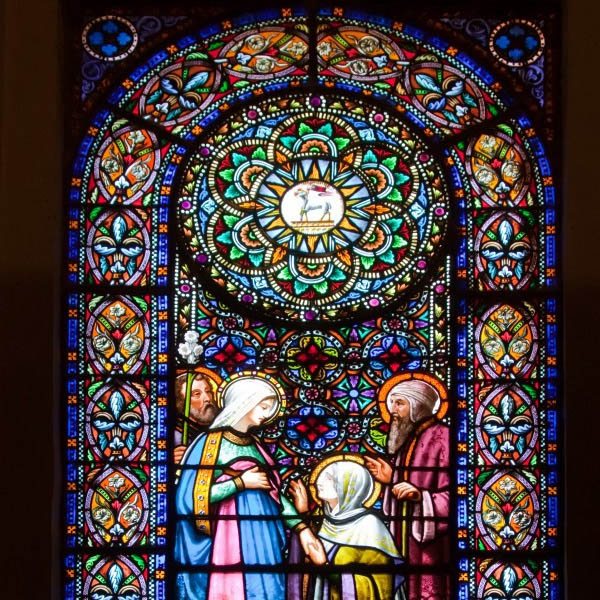

Although Greek continued as the language of the Byzantine Empire, linguistic distribution in the East was more complex. A Greek-speaking majority lived in the Greek peninsula and islands, western Anatolia, major cities, and some coastal areas.[65] Like Greek and Latin, the Thracian language was of Indo-European origin, as were several now-extinct languages in Anatolia attested by Imperial-era inscriptions.[65][78] Albanian is often seen as the descendant of Illyrian, although this hypothesis has been challenged by some linguists, who maintain that it derives from Dacian or Thracian.[89] (Illyrian, Dacian, and Thracian, however, may have formed a subgroup or a Sprachbund; see Thraco-Illyrian.) Various Afroasiatic languages—primarily Coptic in Egypt, and Aramaic in Syria and Mesopotamia—were never replaced by Greek. The international use of Greek, however, was one factor enabling the spread of Christianity, as indicated for example by the use of Greek for the Epistles of Paul.[65]

Several references to Gaulish in late antiquity may indicate that it continued to be spoken. In the second century AD there was an explicit recognition of its usage in some legal manners,[90] soothsaying[91] and pharmacology.[92] Sulpicius Severus, writing in the 5th century AD in Gallia Aquitania, noted bilingualism with Gaulish as the first language.[91] The survival of the Galatian dialect in Anatolia akin to that spoken by the Treveri near Trier was attested by Jerome (331–420), who had first-hand knowledge.[93] Much of historical linguistics scholarship postulates that Gaulish was indeed still spoken as late as the mid to late 6th century in France.[94] Despite considerable Romanization of the local material culture, the Gaulish language is held to have survived and had coexisted with spoken Latin during the centuries of Roman rule of Gaul.[94] The last reference to Galatian was made by Cyril of Scythopolis, claiming that an evil spirit had possessed a monk and rendered him able to speak only in Galatian,[95] while the last reference to Gaulish in France was made by Gregory of Tours between 560 and 575, noting that a shrine in Auvergne which "is called Vasso Galatae in the Gallic tongue" was destroyed and burnt to the ground.[96][94] After the long period of bilingualism, the emergent Gallo-Romance languages including French were shaped by Gaulish in a number of ways; in the case of French these include loanwords and calques (including oui,[97] the word for "yes"),[98][97] sound changes,[99][100] and influences in conjugation and word order.[98][97][101]