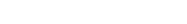

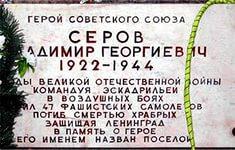

The monument to Serov Vladimir Georgievich

The monument to Serov Vladimir Georgievich is located in the Leningrad region at the place of his death . He served in the 16th reserve regiment. From April 1942 Vladimir Serov — in the army, defended the skies of Leningrad]. By April 1944 — Deputy commander of squadron 159th fighter aviation regiment (275-I fighter aviation division, 13th Air army, Leningrad front), made 203 sorties, in 53 air battles he personally shot down 20 in the group of 6 enemy aircraft.

He died on 26 June 1944 in an air battle on the Karelian isthmus during the Vyborg offensive operation on 26 June 1944.

He was buried in a mass grave in Zelenogorsk.

Awards

By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on 2 August 1944, Lieutenant Serov Vladimir Georgievich awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union (posthumously).

Awarded the order of Lenin, two orders of red banner, order of Alexander Nevsky, world war 1-St degree, medals "For defense of Leningrad"

Made by Dmitri Burkin

Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery

Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery is located in Saint Petersburg, on the Avenue of the Unvanquished (Проспект Непокорённых), dedicated mostly to the victims of the Siege of Leningrad.

The memorial complex designed by Alexander Vasiliev and Yevgeniy Levinson was opened on May 9, 1960. About 420,000 civilians and 50,000 soldiers of the Leningrad Front were buried in 186 mass graves. Near the entrance an eternal flame is located. A marble plate affirms that from September 4, 1941 to January 22, 1944 107,158 air bombs were dropped on the city, 148,478 shells were fired, 16,744 men died, 33,782 were wounded and 641,803 died of starvation.

Mother Motherland

The center of the architectural composition is the bronze monument symbolizing the Mother Motherland, by sculptors V.V. Isaeva and R.К. Taurit.

By granite steps leading down from the Eternal Flame visitors enter the main 480-meter path which leads to the majestic Motherland monument. The words of poet Olga Berggolts are carved on a granite wall located behind this monument:

Here lie Leningraders

Here are citydwellers - men, women, and children

And next to them, Red Army soldiers.

They defended you, Leningrad,

The cradle of the Revolution

With all their lives.

We cannot list their noble names here,

There are so many of them under the eternal protection of granite.

But know this, those who regard these stones:

No one is forgotten, nothing is forgotten.

Made by Daria Synchikova

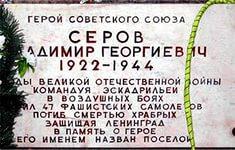

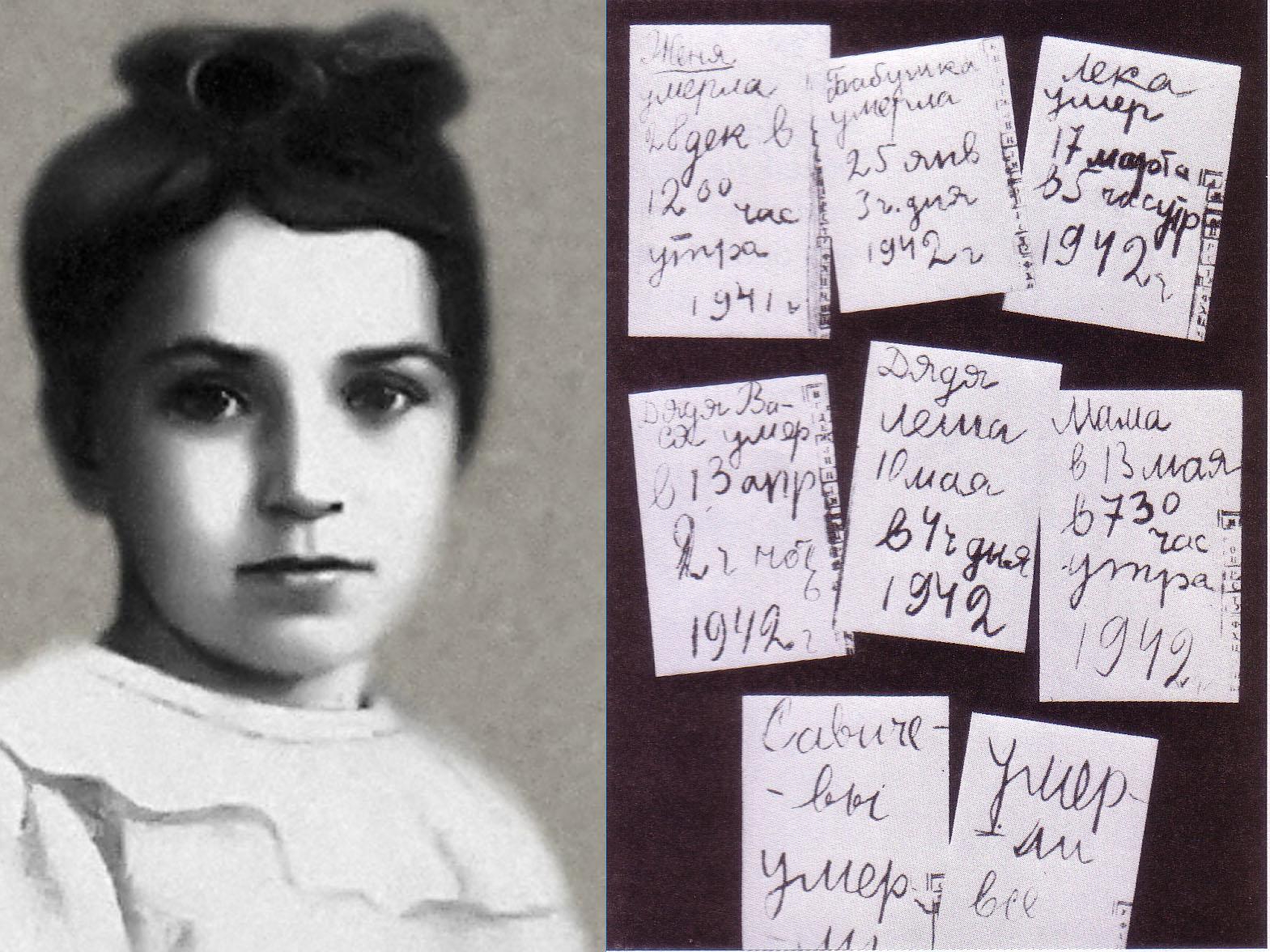

Tanya Savicheva’s Diary

Born on January 23, 1930, she was the youngest child in the family of baker Nikolay Savichev and seamstress Mariya Savicheva. Her father died when Tanya was six, leaving Mariya Savicheva with five children: three girls—Tanya, Zhenya and Nina—and two boys—Mikhail and Leonid.

The family planned to spend the summer of 1941 in the countryside, but the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22 disrupted their plans. All of them, except Mikhail, who had already left, decided to stay in Leningrad. Each of them worked to support the army: Mariya sewed uniforms, Leonid worked as a planner at the Admiralty Plant, Zhenya worked at the munitions factory, Nina worked at the construction of city defences, and Uncle Vasya and Uncle Lesha served in the antil-aircraft defence. Tanya, then 11 years old, dug tranche and put out firebombs.

One day Nina went to work and never came back; she was sent to Lake Ladoga and then urgently evacuated. The family was unaware of this and thought she had died.

After a few days in memory of Nina, Mariya gave to Tanya a small notebook that belonged to her sister and that would later become Tanya's diary. Tanya had a real diary once, a thick notebook where she recorded everything important in her life. She burned it when nothing was left to heat the stove in winter, but she spared her sister's notebook.

The first record in it appeared on December 28. Each day Zhenya got up when it was still dark outside. She walked seven kilometers to the plant, where she worked for two shifts every day making mine cases. After the work she would donate blood. Her weakened body could not endure. She died at the plant where she worked. Then grandmother Yevdokiya died. Then Tanya's brother Leonid. Then, one after another, Uncle Vasya and Uncle Lesha died. Her mother was the last. That time Tanya probably browsed through the pages and added her final remark.

In August 1942, Tanya was one of the 140 children who were rescued from Leningrad and brought to the village of Krasny Bor. All of them survived, except Tanya. Anastasiya Karpova, a teacher in the Krasny Bor orphanage, wrote to Tanya's brother Mikhail, who happened to be outside of Leningrad in 1941: "Tanya is now alive, but she doesn't look healthy. A doctor, who visited her recently, says she is very ill. She needs rest, special care, nutrition, better climate and, most of all, tender motherly care." In May 1944, Tanya was sent to a hospital in Shatki, where she died a month later, on July 1, of intestinal tuberculosis.

According to several sources, one of the documents presented by the Allied prosecutors during the Nuremberg Trials was the small notebook that once belonged to Tanya, but there appears to be no proof of this and an argument against its veracity being that if the diary had been really presented at the Nuremberg Trials it would have never left the court archives.

Nina Savicheva and Mikhail Savichev returned to Leningrad after Word War 2. The diary of Tanya Savicheva is now displayed at the Museum of Leningrad History and a copy is displayed at the Piskareovskoe Memorial Cemetery.

Contents of the diary

Zhenya died on Dec. 28th at 12:00 P.M. 1941

Grandma died on Jan. 25th 3:00 P.M. 1942

Leka died on March 17th at 5:00 A.M. 1942

Uncle Vasya died on Apr. 13th at 2:00 after midnight 1942

Uncle Lesha on May 10th at 4:00 P.M. 1942

Mother on May 13th at 7:30 A.M. 1942

Savichevs died.

Everyone died.

Only Tanya is left.

Made by Yegor Demidov

Pulkovo Boundary

In September 1941, there turned fierce battles against the Nazi troops, rushing toward Leningrad. In January 1944 from the area of the Pulkovo heights in the direction of the Red Village - Ropsha applied the brunt of the enemy, which led to the final defeat of the Nazis in Leningrad.At this crucial sector of the defense of the city there are several monuments."Pulkovo Boundary" (20th kilometer of the Kiev highway).

This place is central to the "Green Belt of Glory" at the Pulkovo Heights. On sloping ground rises a monumental stele with five-meter rectangular protrusions on the ends.

It is lined on all sides with mosaic panels made of white, gray and black granite, and rests on the podium, cut seven flowerbeds. At mosaics depicted episodes in the life of the besieged city. Here on the ground, lined with pine trees, there are two tanks. On a metal stand a granite plaque with the text: "The people of Leningrad, soldiers and militias, women and children, breast defended the cradle of the Great October Revolution - the city of Lenin - a 900-day battle against the fascist hordes, this monument was erected glory workers of the Moscow region in the year of the 50th anniversary Soviet power. October 1967 ".

Opened October 17, 1967. Overall height - 3.85 meters, length - 35 meters.The authors of the first stage of the complex architect Y.N. Lukin and artist A.P. Olkhovich.

Made by Maxim Musibit

Monument to Blockade Tram

Walking down the Strikes Avenue, you can stumble upon an old tram, standing on the side of the road. In fact, it is a monument to the besieged tram, a kind of symbol of courage and valor of Leningrad. The city's first tram appeared on Garden Street in 1907, and it later became a monument to the centenary of the event.

These trams walked through the city in the 1940s and were the main means of transport. During the blockade and the cutting off electricity many cars were not even able to go back to the park and have remained in the streets of the besieged city.

The front line during the war was situated just in four kilometers from the place where now stands the monument. It is built from the Leningrad tram cars stuffed with stones, anti-tank barricades.

These trams walked through the city in the 1940s and were the main mode of transport. When the blockade and cut off electricity, many cars were not even able to go back to the park and have remained in the streets of the besieged city. The front line during the war took place just four kilometers from the place where now stands the monument. It is built from the Leningrad tram cars stuffed with stones, anti-tank barricades.

Made by Mariya Yepifanova

Monument "Children of the blockade."

In St. Petersburg, a monument to the children of the blockade. Today, on the Day of Remembrance of the blockade on Vasilevsky Island unveiled a monument to the children of besieged Leningrad. The monument was erected in the apple orchard, which in 1953 put the students one of the city schools in memory of the children of the besieged city. Authors - sculptor and architect Galina Dodonova Vladimir Reppo.

"We are opening today monument, which has no equal in our city - said Governor Valentina Matvienko. - It is a monument to the heroism and courage of the young Leningrad. " "The word" children "and" blockade "is difficult to put together. But the war has bound them together. More than four hundred thousand children appeared in the besieged Leningrad. And not all managed to take the road of life. Toddler siege of Leningrad can be called angels besieged city, "- said the governor.

She said that last year the city, in response to requests from residents of Vasilevsky Island, gave money for the restoration of the garden. Has been renovated, paved paths, planted with flowers. It was also decided to establish a monument to him children blockade, said the press service of the governor.

At the opening ceremony of the monument to the students gathered near by schools, veterans of war, blockade. In memory of those killed during the siege of children held a minute's silence. To the monument were laid flowers and toys. Everyone who came to honor the memory of young Leningrad, treated apples from this memorial garden.

Made by Margarita Ferdman