Roman Empire

Society[edit] Further information: Ancient Roman society

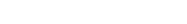

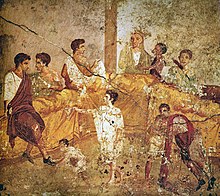

A multigenerational banquet depicted on a wall painting from Pompeii (1st century AD)

The Roman Empire was remarkably multicultural, with "a rather astonishing cohesive capacity" to create a sense of shared identity while encompassing diverse peoples within its political system over a long span of time.[102] The Roman attention to creating public monuments and communal spaces open to all—such as forums, amphitheatres, racetracks and baths—helped foster a sense of "Romanness".[103]

Roman society had multiple, overlapping social hierarchies that modern concepts of "class" in English may not represent accurately.[104] The two decades of civil war from which Augustus rose to sole power left traditional society in Rome in a state of confusion and upheaval,[105] but did not effect an immediate redistribution of wealth and social power. From the perspective of the lower classes, a peak was merely added to the social pyramid.[106] Personal relationships—patronage, friendship (amicitia), family, marriage—continued to influence the workings of politics and government, as they had in the Republic.[107] By the time of Nero, however, it was not unusual to find a former slave who was richer than a freeborn citizen, or an equestrian who exercised greater power than a senator.[108]

The blurring or diffusion of the Republic's more rigid hierarchies led to increased social mobility under the Empire,[109][110] both upward and downward, to an extent that exceeded that of all other well-documented ancient societies.[111] Women, freedmen, and slaves had opportunities to profit and exercise influence in ways previously less available to them.[112] Social life in the Empire, particularly for those whose personal resources were limited, was further fostered by a proliferation of voluntary associations and confraternities (collegia and sodalitates) formed for various purposes: professional and trade guilds, veterans' groups, religious sodalities, drinking and dining clubs,[113] performing arts troupes,[114] and burial societies.[115]

Legal status

[edit] Main articles: Status in Roman legal system and Roman citizenship

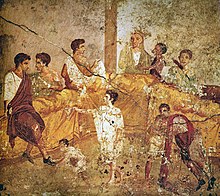

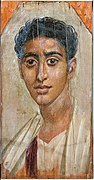

Citizen of Roman Egypt (Fayum mummy portrait)

According to the jurist Gaius, the essential distinction in the Roman "law of persons" was that all human beings were either free (liberi) or slaves (servi).[116][117] The legal status of free persons might be further defined by their citizenship. Most citizens held limited rights (such as the ius Latinum, "Latin right"), but were entitled to legal protections and privileges not enjoyed by those who lacked citizenship. Free people not considered citizens, but living within the Roman world, held status as peregrini, non-Romans.[118] In 212 AD, by means of the edict known as the Constitutio Antoniniana, the emperor Caracalla extended citizenship to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire. This legal egalitarianism would have required a far-reaching revision of existing laws that had distinguished between citizens and non-citizens.[119]

Women in Roman law

[edit] Main article: Women in ancient Rome

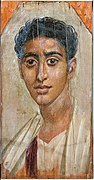

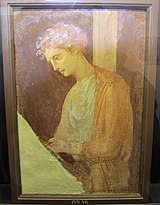

Left image: Roman fresco of an auburn maiden reading a text, Pompeian Fourth Style (60–79 AD), Pompeii, Italy

Right image: Bronze statuette (1st century AD) of a young woman reading, based on a Hellenistic original

Dressing of a priestess or bride, Roman fresco from Herculaneum, Italy (30–40 AD)

Freeborn Roman women were considered citizens throughout the Republic and Empire, but did not vote, hold political office, or serve in the military. A mother's citizen status determined that of her children, as indicated by the phrase ex duobus civibus Romanis natos ("children born of two Roman citizens").[n 10] A Roman woman kept her own family name (nomen) for life. Children most often took the father's name, but in the Imperial period sometimes made their mother's name part of theirs, or even used it instead.[120]

The archaic form of manus marriage in which the woman had been subject to her husband's authority was largely abandoned by the Imperial era, and a married woman retained ownership of any property she brought into the marriage. Technically she remained under her father's legal authority, even though she moved into her husband's home, but when her father died she became legally emancipated.[121] This arrangement was one of the factors in the degree of independence Roman women enjoyed relative to those of many other ancient cultures and up to the modern period:[122][123] although she had to answer to her father in legal matters, she was free of his direct scrutiny in her daily life,[124] and her husband had no legal power over her.[125] Although it was a point of pride to be a "one-man woman" (univira) who had married only once, there was little stigma attached to divorce, nor to speedy remarriage after the loss of a husband through death or divorce.[126]

Girls had equal inheritance rights with boys if their father died without leaving a will.[127][128][129] A Roman mother's right to own property and to dispose of it as she saw fit, including setting the terms of her own will, gave her enormous influence over her sons even when they were adults.[130]

As part of the Augustan programme to restore traditional morality and social order, moral legislation attempted to regulate the conduct of men and women as a means of promoting "family values". Adultery, which had been a private family matter under the Republic, was criminalized,[131] and defined broadly as an illicit sex act (stuprum) that occurred between a male citizen and a married woman, or between a married woman and any man other than her husband.[n 11] Childbearing was encouraged by the state: a woman who had given birth to three children was granted symbolic honours and greater legal freedom (the ius trium liberorum).

Because of their legal status as citizens and the degree to which they could become emancipated, women could own property, enter contracts, and engage in business,[132][133] including shipping, manufacturing, and lending money. Inscriptions throughout the Empire honour women as benefactors in funding public works, an indication they could acquire and dispose of considerable fortunes; for instance, the Arch of the Sergii was funded by Salvia Postuma, a female member of the family honoured, and the largest building in the forum at Pompeii was funded by Eumachia, a priestess of Venus.[134]

Slaves and the law

[edit] Main article: Slavery in ancient Rome

At the time of Augustus, as many as 35% of the people in Italy were slaves,[135] making Rome one of five historical "slave societies" in which slaves constituted at least a fifth of the population and played a major role in the economy.[136] Slavery was a complex institution that supported traditional Roman social structures as well as contributing economic utility.[137] In urban settings, slaves might be professionals such as teachers, physicians, chefs, and accountants, in addition to the majority of slaves who provided trained or unskilled labour in households or workplaces. Agriculture and industry, such as milling and mining, relied on the exploitation of slaves. Outside Italy, slaves made up on average an estimated 10 to 20% of the population, sparse in Roman Egypt but more concentrated in some Greek areas. Expanding Roman ownership of arable land and industries would have affected preexisting practices of slavery in the provinces.[138][139] Although the institution of slavery has often been regarded as waning in the 3rd and 4th centuries, it remained an integral part of Roman society until the 5th century. Slavery ceased gradually in the 6th and 7th centuries along with the decline of urban centres in the West and the disintegration of the complex Imperial economy that had created the demand for it.[140]

Slave holding writing tablets for his master (relief from a 4th-century sarcophagus)

Laws pertaining to slavery were "extremely intricate".[141] Under Roman law, slaves were considered property and had no legal personhood. They could be subjected to forms of corporal punishment not normally exercised on citizens, sexual exploitation, torture, and summary execution. A slave could not as a matter of law be raped since rape could be committed only against people who were free; a slave's rapist had to be prosecuted by the owner for property damage under the Aquilian Law.[142][143] Slaves had no right to the form of legal marriage called conubium, but their unions were sometimes recognized, and if both were freed they could marry.[144] Following the Servile Wars of the Republic, legislation under Augustus and his successors shows a driving concern for controlling the threat of rebellions through limiting the size of work groups, and for hunting down fugitive slaves.[145]

Technically, a slave could not own property,[146] but a slave who conducted business might be given access to an individual account or fund (peculium) that he could use as if it were his own. The terms of this account varied depending on the degree of trust and co-operation between owner and slave: a slave with an aptitude for business could be given considerable leeway to generate profit and might be allowed to bequeath the peculium he managed to other slaves of his household.[147] Within a household or workplace, a hierarchy of slaves might exist, with one slave in effect acting as the master of other slaves.[148]

Over time slaves gained increased legal protection, including the right to file complaints against their masters. A bill of sale might contain a clause stipulating that the slave could not be employed for prostitution, as prostitutes in ancient Rome were often slaves.[149] The burgeoning trade in eunuch slaves in the late 1st century AD prompted legislation that prohibited the castration of a slave against his will "for lust or gain."[150][151]

Roman slavery was not based on race.[152][153] Slaves were drawn from all over Europe and the Mediterranean, including Gaul, Hispania, Germany, Britannia, the Balkans, Greece... Generally, slaves in Italy were indigenous Italians,[154] with a minority of foreigners (including both slaves and freedmen) born outside of Italy estimated at 5% of the total in the capital at its peak, where their number was largest. Those from outside of Europe were predominantly of Greek descent, while the Jewish ones never fully assimilated into Roman society, remaining an identifiable minority. These slaves (especially the foreigners) had higher mortality rates and lower birth rates than natives, and were sometimes even subjected to mass expulsions.[155] The average recorded age at death for the slaves of the city of Rome was extraordinarily low: seventeen and a half years (17.2 for males; 17.9 for females).[156]

During the period of Republican expansionism when slavery had become pervasive, war captives were a main source of slaves. The range of ethnicities among slaves to some extent reflected that of the armies Rome defeated in war, and the conquest of Greece brought a number of highly skilled and educated slaves into Rome. Slaves were also traded in markets and sometimes sold by pirates. Infant abandonment and self-enslavement among the poor were other sources.[138] Vernae, by contrast, were "homegrown" slaves born to female slaves within the urban household or on a country estate or farm. Although they had no special legal status, an owner who mistreated or failed to care for his vernae faced social disapproval, as they were considered part of his familia, the family household, and in some cases might actually be the children of free males in the family.[157][158]

Talented slaves with a knack for business might accumulate a large enough peculium to justify their freedom, or be manumitted for services rendered. Manumission had become frequent enough that in 2 BC a law (Lex Fufia Caninia) limited the number of slaves an owner was allowed to free in his will.[159]

Freedmen

[edit]

Cinerary urn for the freedman Tiberius Claudius Chryseros and two women, probably his wife and daughter

Rome differed from Greek city-states in allowing freed slaves to become citizens. After manumission, a slave who had belonged to a Roman citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote.[160] A slave who had acquired libertas was a libertus ("freed person," feminine liberta) in relation to his former master, who then became his patron (patronus): the two parties continued to have customary and legal obligations to each other. As a social class generally, freed slaves were libertini, though later writers used the terms libertus and libertinus interchangeably.[161][162]

A libertinus was not entitled to hold public office or the highest state priesthoods, but he could play a priestly role in the cult of the emperor. He could not marry a woman from a family of senatorial rank, nor achieve legitimate senatorial rank himself, but during the early Empire, freedmen held key positions in the government bureaucracy, so much so that Hadrian limited their participation by law.[162] Any future children of a freedman would be born free, with full rights of citizenship.

The rise of successful freedmen—through either political influence in imperial service or wealth—is a characteristic of early Imperial society. The prosperity of a high-achieving group of freedmen is attested by inscriptions throughout the Empire, and by their ownership of some of the most lavish houses at Pompeii, such as the House of the Vettii. The excesses of nouveau riche freedmen were satirized in the character of Trimalchio in the Satyricon by Petronius, who wrote in the time of Nero. Such individuals, while exceptional, are indicative of the upward social mobility possible in the Empire.

Census rank

[edit] See also: Senate of the Roman Empire, Equestrian order, and Decurion (administrative)

The Latin word ordo (plural ordines) refers to a social distinction that is translated variously into English as "class, order, rank," none of which is exact. One purpose of the Roman census was to determine the ordo to which an individual belonged. The two highest ordines in Rome were the senatorial and equestrian. Outside Rome, the decurions, also known as curiales (Greek bouleutai), were the top governing ordo of an individual city.

Fragment of a sarcophagus depicting Gordian III and senators (3rd century)

"Senator" was not itself an elected office in ancient Rome; an individual gained admission to the Senate after he had been elected to and served at least one term as an executive magistrate. A senator also had to meet a minimum property requirement of 1 million sestertii, as determined by the census.[163][164] Nero made large gifts of money to a number of senators from old families who had become too impoverished to qualify. Not all men who qualified for the ordo senatorius chose to take a Senate seat, which required legal domicile at Rome. Emperors often filled vacancies in the 600-member body by appointment.[165][166] A senator's son belonged to the ordo senatorius, but he had to qualify on his own merits for admission to the Senate itself. A senator could be removed for violating moral standards: he was prohibited, for instance, from marrying a freedwoman or fighting in the arena.[167]

In the time of Nero, senators were still primarily from Rome and other parts of Italy, with some from the Iberian peninsula and southern France; men from the Greek-speaking provinces of the East began to be added under Vespasian.[168] The first senator from the most eastern province, Cappadocia, was admitted under Marcus Aurelius.[169] By the time of the Severan dynasty (193–235), Italians made up less than half the Senate.[170] During the 3rd century, domicile at Rome became impractical, and inscriptions attest to senators who were active in politics and munificence in their homeland (patria).[167]

Senators had an aura of prestige and were the traditional governing class who rose through the cursus honorum, the political career track, but equestrians of the Empire often possessed greater wealth and political power. Membership in the equestrian order was based on property; in Rome's early days, equites or knights had been distinguished by their ability to serve as mounted warriors (the "public horse"), but cavalry service was a separate function in the Empire.[n 12] A census valuation of 400,000 sesterces and three generations of free birth qualified a man as an equestrian.[171] The census of 28 BC uncovered large numbers of men who qualified, and in 14 AD, a thousand equestrians were registered at Cadiz and Padua alone.[n 13][172] Equestrians rose through a military career track (tres militiae) to become highly placed prefects and procurators within the Imperial administration.[173][174]

The rise of provincial men to the senatorial and equestrian orders is an aspect of social mobility in the first three centuries of the Empire. Roman aristocracy was based on competition, and unlike later European nobility, a Roman family could not maintain its position merely through hereditary succession or having title to lands.[175][176] Admission to the higher ordines brought distinction and privileges, but also a number of responsibilities. In antiquity, a city depended on its leading citizens to fund public works, events, and services (munera), rather than on tax revenues, which primarily supported the military. Maintaining one's rank required massive personal expenditures.[177] Decurions were so vital for the functioning of cities that in the later Empire, as the ranks of the town councils became depleted, those who had risen to the Senate were encouraged by the central government to give up their seats and return to their hometowns, in an effort to sustain civic life.[178]

In the later Empire, the dignitas ("worth, esteem") that attended on senatorial or equestrian rank was refined further with titles such as vir illustris, "illustrious man".[179] The appellation clarissimus (Greek lamprotatos) was used to designate the dignitas of certain senators and their immediate family, including women.[180] "Grades" of equestrian status proliferated. Those in Imperial service were ranked by pay grade (sexagenarius, 60,000 sesterces per annum; centenarius, 100,000; ducenarius, 200,000). The title eminentissimus, "most eminent" (Greek exochôtatos) was reserved for equestrians who had been Praetorian prefects. The higher equestrian officials in general were perfectissimi, "most distinguished" (Greek diasêmotatoi), the lower merely egregii, "outstanding" (Greek kratistos).[181]

Unequal justice

[edit]

Condemned man attacked by a leopard in the arena (3rd-century mosaic from Tunisia)

As the republican principle of citizens' equality under the law faded, the symbolic and social privileges of the upper classes led to an informal division of Roman society into those who had acquired greater honours (honestiores) and those who were humbler folk (humiliores). In general, honestiores were the members of the three higher "orders," along with certain military officers.[182][183] The granting of universal citizenship in 212 seems to have increased the competitive urge among the upper classes to have their superiority over other citizens affirmed, particularly within the justice system.[183][184][185] Sentencing depended on the judgment of the presiding official as to the relative "worth" (dignitas) of the defendant: an honestior could pay a fine when convicted of a crime for which an humilior might receive a scourging.[183]

Execution, which had been an infrequent legal penalty for free men under the Republic even in a capital case,[186][187] could be quick and relatively painless for the Imperial citizen considered "more honourable", while those deemed inferior might suffer the kinds of torture and prolonged death previously reserved for slaves, such as crucifixion and condemnation to the beasts as a spectacle in the arena.[188] In the early Empire, those who converted to Christianity could lose their standing as honestiores, especially if they declined to fulfil the religious aspects of their civic responsibilities, and thus became subject to punishments that created the conditions of martyrdom.[183][189]

Government and military